TR’S FIVE BIG POST-PRESIDENTIAL ADVENTURES

When Theodore Roosevelt left the White House in March 1909, he was only 50 years old—still teeming with energy, ambition, and a restless desire to test himself. While many former presidents slip quietly into retirement, Roosevelt launched into some of the boldest pursuits of his life.

Although his reasons varied for each of his five big expeditions and trips post-presidency, each was an opportunity to escape the humdrum of daily life and instead pursue adventure with the same ferocity that he once brought to the presidency, roaming across continents and seas in search of danger, discovery, and renewal.

In the decade that followed his presidency, Roosevelt’s life became a string of daring exploits—part science, part sport, and entirely in keeping with his creed that it was better to “dare mighty things” than to live in timid ease.

1. INTO THE HEART OF AFRICA: THE SMITHSONIAN-ROOSEVELT EXPEDITION (1909-1910)

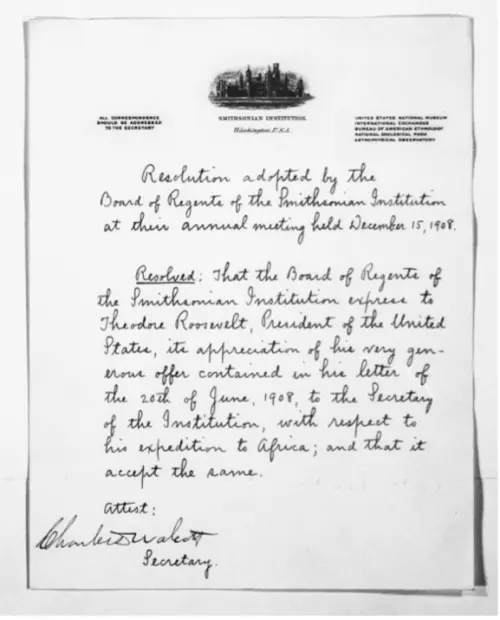

Roosevelt’s first great adventure after leaving office was the Smithsonian-Roosevelt Expedition to Africa. When he knew in 1908 the end of his presidency was looming, he began to plan his next big adventure, writing in a letter that his “trip to Africa will merely be that of an elderly retired official.”

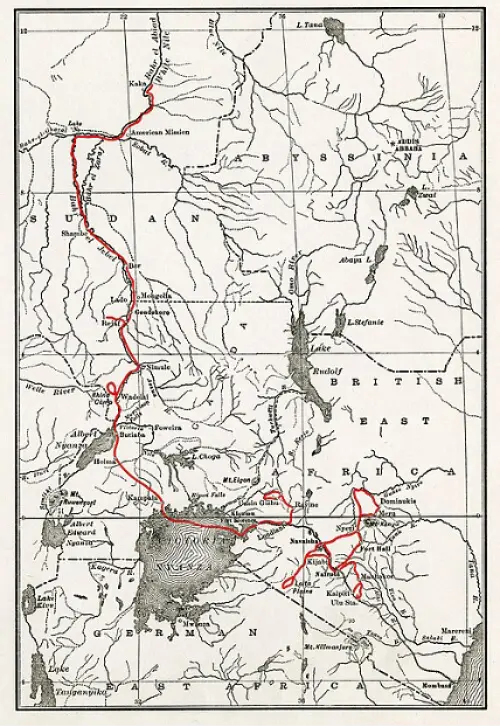

Backed by the Smithsonian Institution, Roosevelt, his son Kermit, and a team of naturalists set off in April 1909 across East Africa (modern-day Kenya and Uganda), the Congo, and Sudan.

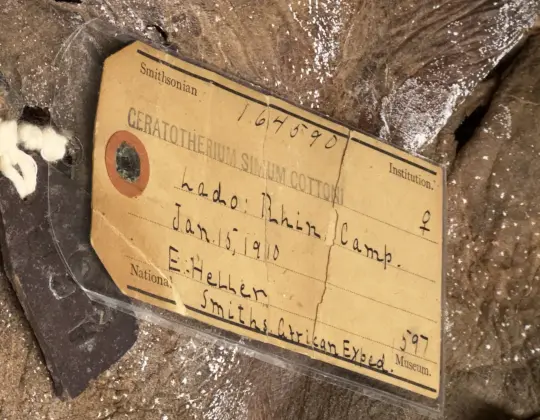

The expedition lasted nearly a year and gathered thousands of plant and animal specimens—so many, in fact, that Smithsonian scientists were still cataloguing them decades later. Moreover, the safari was no mere sightseeing trip.

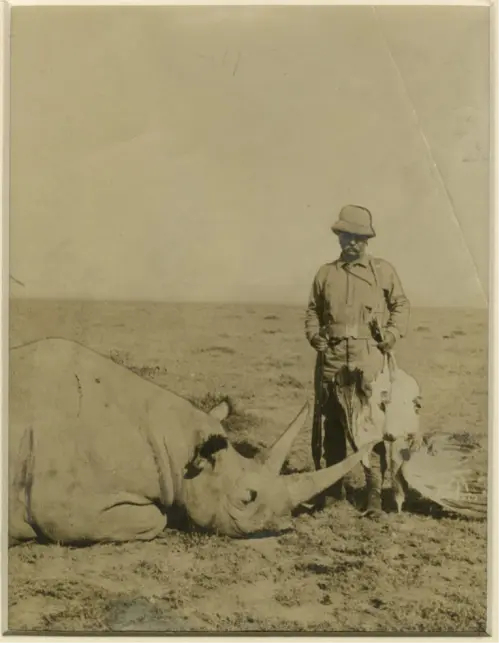

Roosevelt, his son Kermit, and the team faced sweltering heat, dangerous diseases, and the ever-present threat of charging rhinos, elephants, and lions. Roosevelt himself relished every moment, rising before dawn to record observations or stalk game.

The party gathered over 11,000 specimens for museums and universities from beetles and birds to lions and elephants. Roosevelt himself killed or collected over 250 animals, including some of Africa’s largest game.

In his book detailing the expedition, African Game Trails, Roosevelt listed the larger animals that he or Kermit killed, including 10 African buffalo, 9 black rhino, 6 cheetah, 12 elephant, 3 leopard, 18 lion, and 97 white rhino.

While modern readers may cringe at the scale of the hunting, at the time it was viewed as a major contribution to science, since the animals became specimens for museums and universities. In reality, as Smithsonian mammalogist Darrin Lunde noted, “[Roosevelt] had personally killed 296 animals, and his son Kermit killed 216 more, but that was not even a tenth of what they might have killed had they been so inclined.”

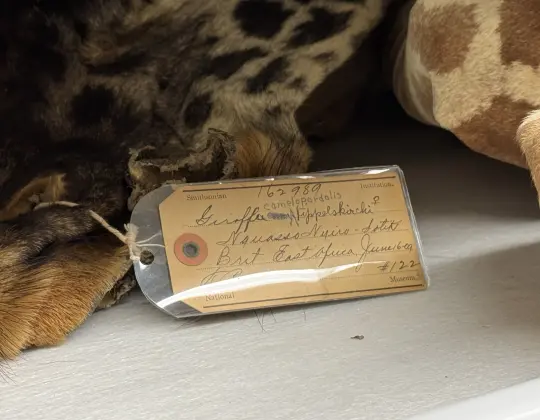

The specimens the Smithsonian-Roosevelt Expedition collected are still used to this day to understand the biodiversity that existed in that region of Africa during Roosevelt’s time and how conservation efforts might help the area return to the biodiversity it had over 100 years ago.

This journey cemented Roosevelt’s image as the great outdoorsman-president. His book African Game Trails, published when he returned in 1910, was a vivid account of the expedition. It became a bestseller. The trip was also a personal triumph: Roosevelt proved that he was still up for a physical challenge.

The images in the photo gallery below are courtesy of Matt Briney taken of objects in the collection at the Museum Support Center, Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. Some of these items will be displayed in the exhibits at the Theodore Roosevelt Presidential Library.

2. EXPLORING THE RIVER OF DOUBT: THE ROOSEVELT-RONDON EXPEDITION (1914)

If Africa tested his stamina, South America nearly broke him. What began as a series of lectures—Roosevelt had been invited on a speaking tour—turned into another big adventure for Roosevelt, this time in the Amazon. Reeling from the loss of the 1912 presidential election, Roosevelt sought adventure to get away from the depression he faced at his home, Sagamore Hill.

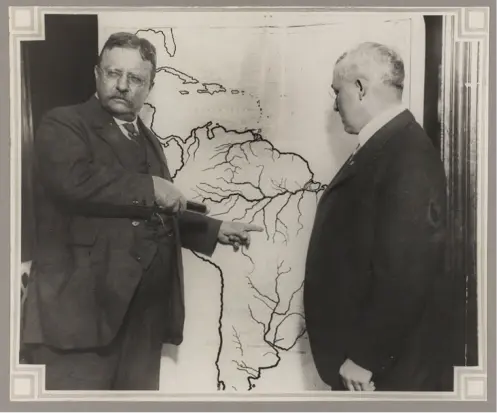

Roosevelt joined Brazilian explorer and military officer Cândido Mariano da Silva Rondon on a perilous expedition to map the Rio da Dúvida, or River of Doubt, an uncharted tributary of the Amazon, with several other Americans, including his son Kermit, and a team of Brazilian camaradas.

As Roosevelt wrote in a letter to his sister Anna Roosevelt Cowles on November 11, 1913, “Thanks to the Brazilian Government, we have an opportunity of going down an unknown river . . . so if things go well we may be able to do something really worth while.”

On February 27, 1914, Roosevelt, Rondon, and the twenty other men on the expedition pushed off at slightly past noon. The journey quickly turned into a battle for survival.

The men hacked through unyielding rainforest, fought destructive rapids that smashed their canoes, and endured malaria, starvation, and exhaustion. One of the camaradas was even murdered by a fellow camarada.

Roosevelt himself faced his own challenges: gashing his right shin, developing a severe infection, and being stricken with fever. At one point he urged his companions to leave him behind so they might live. They refused. His son Kermit, who had come along, played a vital role in keeping him alive.

After months of near-disaster, the expedition emerged, having mapped the 1,000-mile river, which was renamed the Roosevelt River in the former president’s honor. The ordeal permanently weakened Roosevelt’s health, but it added another legendary chapter to his already larger-than-life story.

3. PROTECTING THE BIRDS: A PILGRIMAGE TO THE BRETON AND CHANDELEUR ISLANDS (1915)

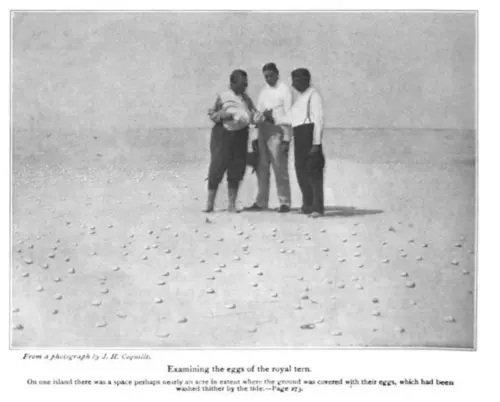

Roosevelt’s adventures were not only about testing his strength—they also reflected his passion for conservation. In June 1915, he made a special journey to the Breton and Chandeleur Islands, small barrier islands off Louisiana’s coast near New Orleans, via boat under the auspices of the Audubon Society.

Years earlier, as president, he had established what is known today as Breton National Wildlife Refuge in 1904 as the nation’s second federal bird reserve, part of his sweeping conservation program that created 52 bird reservations, now called wildlife refuges.

Leaving at 4 a.m. on June 8, 1915, the day after arriving in Pass Christian, Mississippi, Roosevelt boarded the Daisy, a boat provided by the Louisiana State Conservation Commission for a four-day trip to the Breton and Chandeleur Islands. The Audubon Society’s boat, the Royal Tern, also came along.

On Breton Island, Roosevelt watched thousands of pelicans, herons, and gulls nesting in the marshes and along the sandbars. He was visibly delighted to see the refuge thriving, a living symbol of his efforts to protect America’s natural heritage. A newspaper article reported Roosevelt saying after his return, “I have had a bully time and enjoyed every minute of the trip.”

Ever the writer, Roosevelt detailed his experiences in a Scribner’s Magazine article entitled “The Bird Refuges of Louisiana,” published in March 1916. He went into great detail about a plethora of birds from frigate birds to royal terns, including much discussion about their eggs.

As Roosevelt wrote near the end of the magazine article, “I was very glad to have seen this bird refuge. With care and protection the birds will increase and grow tamer and tamer, until it will be possible for any one to make trips among these reserves and refuges, and to see as much as we saw, at even closer quarters. No sight more beautiful and more interesting could be imagined.”

Breton Island was the only wildlife refuge, a concept that Roosevelt created during his presidency, that the former president ever visited. And it was memorialized in a 15-minute silent conservation film entitled “Roosevelt: Friend of the Birds,” produced by Caroline Gentry for the Roosevelt Memorial Association, which has helped to perpetuate Roosevelt’s legacy of conservation.

Roosevelt’s visit to what is today Breton National Wildlife Refuge is a good reminder that he was not only a hunter and explorer but also one of the greatest conservationists of his time. The spectacle of teeming birdlife on the Gulf Coast was every bit as thrilling to him as the lions of Africa or the jaguars of Brazil.

4. ROOSEVELT’S FINAL BIG GAME HUNT: MOOSE HUNTING IN THE CANADIAN WILDERNESS (1915)

That same year in September 1915, Roosevelt headed to the Canadian wilderness to take his mind off his frustration with President Woodrow Wilson and the president’s insistence on keeping the United States out of World War I. Roosevelt joined his old friend Alexander Lambert at the Tourilli Club, a remote lodge northwest of Quebec City, surrounded by rugged forests and cold rivers.

As Roosevelt wrote in a Scribner’s Magazine article entitled “A Curious Experience,” “I had expected to enjoy the great northern woods, and the sight of beaver, moose, and caribou; but I had not expected any hunting experience worth mentioning.”

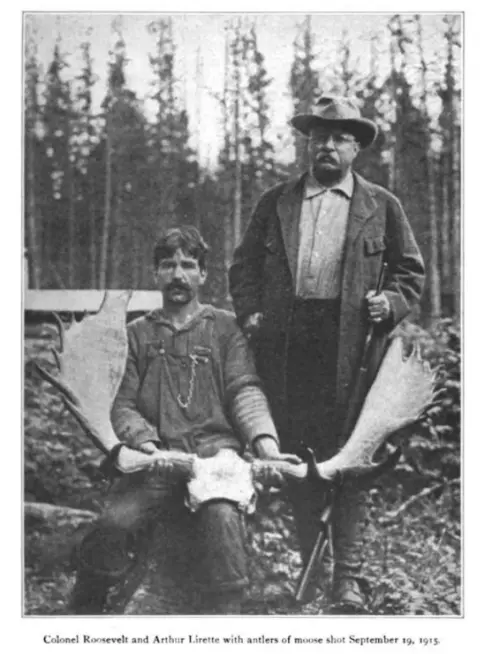

After several days admiring the wildlife, Roosevelt headed northeast toward lakes that were seldom visited with guides Arthur Lirette and Odillon Genest. He wasn’t hunting for a trophy but instead intended to procure food to eat. Roosevelt’s license permitted him one bull moose and two caribou.

Just 25 minutes after breakfast on September 19, 1915, Roosevelt succeed in killing a bull caribou near the end of the first portage—though he missed with his first shot. The next day, Roosevelt succeeded in killing a bull moose—again missing with his first shot. Roosevelt called it a “red-letter day, of the ordinary hunting red-letter type,” or a day of special significance of the “ordinary hunting type.”

Half a mile from the portage landing that led toward the cabin where Roosevelt was staying with his guides, they saw a larger bull moose. They started to paddle toward land away from the moose, but the moose followed along the shore after them. They reversed course, and the moose continued to follow them. They yelled, but to no avail. According to Roosevelt, the moose “evidently meant mischief.”

For over an hour, the moose kept Roosevelt and his guides from coming to shore, no matter where they tried to land. Finally, the moose disappeared. Roosevelt and his guides cautiously landed and started down the trail, ready to shoot the moose if attacked. It did.

Roosevelt attempted to frighten him by first shooting over his head, but when that did not work, he fired four times and finally killed the bull moose. Because his license did not permit killing more than one bull moose, Roosevelt submitted an affidavit explaining why he was compelled to kill a second bull moose to the Minister of the Department of Colonization, Mines & Fisheries. It was accepted. (Roosevelt even received a complimentary non-resident hunting license for 1916 from the minister.)

The three-week-long trip was not Roosevelt’s most successful hunt and, in some ways, was one of his worst. As Roosevelt wrote in a letter to his son Kermit, “I went off with the dear [Alexander] Lambert for three weeks, at their club, north of Quebec, and had bull luck, altho [sic] I shot atrociously, and saw and [walked] so badly that I shall never again make an exhibition of myself by going on a hunting trip. I’m past it!” And he never did—as this was Roosevelt’s last big game hunt before he died.

Perhaps fittingly, with this hunt being Roosevelt’s last big game hunt, there is an illustration of Roosevelt’s Springfield rifle no. 6000, model 1903 in his Scribner’s article with a list of all the “heavy game” he had killed with it, including moose and caribou. He notes that the rifle was “now a retired veteran” and had been his “chief hunting-rifle for the last dozen years on three continents.”

5. WRESTLING A SEA MONSTER: THE MANTA RAY HUNT (1917)

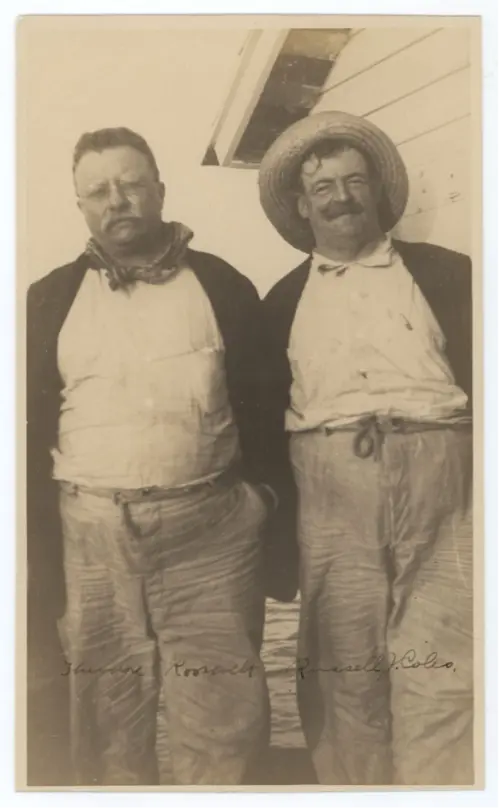

Even as his health declined, Theodore Roosevelt sought new challenges. After reading about renown ichthyologist Russell J. Coles’s description of hunting a giant manta ray, Roosevelt himself wanted to take part—and reached out to Coles.

As he wrote in a November 2, 1916 letter to Coles, “Never have I done anything as interesting as you have done with your Devil-Fish hunting, and your harpooning and fishing for the White Shark, and indeed other sharks. This is tackling the big game of the sea.” Coles was happy to oblige, and a trip was planned for March 1917.

Roosevelt, Coles, and a small crew headed for the Gulf of Mexico off the coast of Florida near Captiva Island about 30 miles south of Punta Gorda, Florida. Armed with harpoons and ropes, Roosevelt hoped to capture one of these enormous “devilfish,” often with a wingspan of 15 feet and a weight of close to a ton.

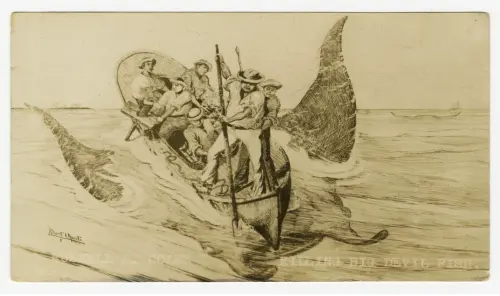

The first day Roosevelt, Coles, and the crew went in search of manta rays, they found one. As the guest of honor, Roosevelt threw the harpoon but missed—despite practicing at his home in Oyster Bay leading up to the trip. Soon thereafter, they saw several more. This time, when Roosevelt threw the harpoon, it made contact.

After the crew hauled this manta ray to shore, they realized it was not one of the larger rays, but merely one of average size. They headed out again to find a larger ray. Again, Roosevelt threw the harpoon and speared the manta ray successfully.

The fight was spectacular. Once struck, the manta dragged their boat in circles, thrashing and diving with enormous force. Roosevelt, exhilarated, joined in the struggle, pulling on the ropes as the men battled the leviathan for 26 minutes. At last they hauled it ashore, a massive black shape that dwarfed the men around it.

When the crew returned to shore, they found that the larger ray had a wingspan of sixteen feet, eight inches as compared to the other ray, which had a wingspan of thirteen feet, two inches. Delighted by his success, Roosevelt did not kill any more giant manta rays, calling them “huge, rare creatures” and instead observed the wildlife off the coast of Florida.

Newspapers marveled at the story, presenting it as Roosevelt’s latest conquest, proof that even in his late fifties, the former president was still chasing—and catching—giants.

A LIFE LIVED TO THE FULLEST

Theodore Roosevelt’s post-presidential years were unlike those of any other American president. Instead of retreating into quiet memoir writing—though he did do some writing—he threw himself into an African safari, an Amazonian exploration, a Canadian wilderness hunt, and even a sea battle with giant manta rays. He also revisited a conservation landmark of his presidency, demonstrating that his legacy was not just one of hunting and killing but also of preservation and scientific advancement.

By the time of his death in 1919, Roosevelt’s body was worn down, but his reputation as a man of action had only grown. He had proven that life after the presidency could be as daring, as meaningful, and as full of adventure as the years he spent in office.