WHAT TR THOUGHT ABOUT “TEDDY”

“There is a mark of widespread recognition, of fine quality and good heart that comes to few public men—that came to him—the affectionate nickname. He always was and always will be ‘Teddy dear’ to all America.”

~Theodore Roosevelt, Typical American, by Thomas Herbert Russell (1919)

For many Americans, the name “Teddy Roosevelt” rolls off the tongue as easily as “George Washington” or “Abe Lincoln.” It feels familiar, friendly, almost affectionate.

The nickname “Teddy” has become so attached to the image of our twenty-sixth president—charging up Kettle Hill, championing conservation, and grinning beneath his pince-nez—that it seems impossible to disassociate Roosevelt from it.

Yet, the man himself did not share the public’s fondness for this diminutive. In fact, TR bristled at being called “Teddy” and tried, often unsuccessfully, to keep it at arm’s length. Here is the history of this notorious American faux pas.

TR’S NICKNAMES AS A CHILD AND YOUNG ADULT

Born in 1858 into a wealthy New York household, “Teddy” wasn’t a nickname TR was known by.

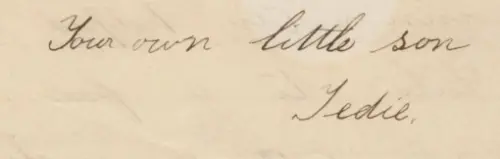

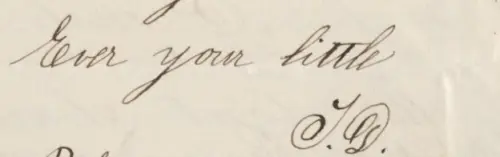

Instead, his family nickname was “Teedie,” [pronounced tee-dee] alternatively spelled “Tedie” or even “T.D.”

As Jacob Riis, social reformer and friend to TR, said of him: “[I]t is doubtful if the President ever was called ‘Teddy’ when he was a boy. He used to be ‘Teedy’ in the family circle and at Harvard he was ‘Ted,’ while among the intimates of his manhood he is always called ‘Theodore.’”

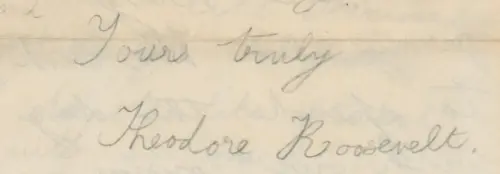

In his earliest letters, TR signed his name formally as “Theodore” as can be seen in letters he wrote in the late 1860s.

For example, see a letter TR wrote to his parents and sister Corinne “Conie” in 1868 when TR was nine years old.

Likewise, in a letter written around the same time frame to his childhood friend and later wife, Edith Kermit Carow, TR also signed his name as “Theodore.”

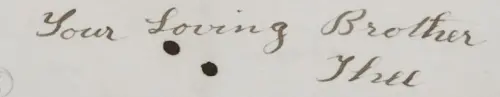

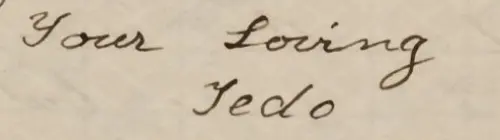

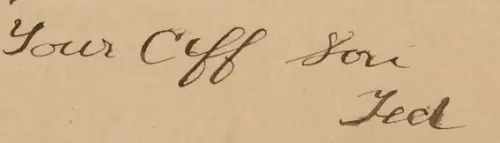

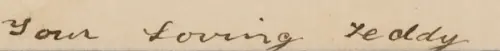

But by the early 1870s, TR started to sign some of his letters with his family nickname. (He also signed some of his letters with a “Jr.” at the end, such as “T. Roosevelt Jr.”)

According to Orison Swett Marden in Little Visits with Great Americans (1905), around the time TR was 15 years old in 1873, Mittie thought that TR’s family nickname of “Teedie” should be “replaced by something more dignified, and so it was decided, in family council, that he should be addressed as Theodore.”

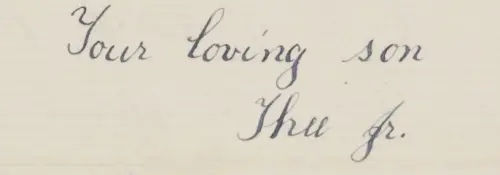

It was also around this time in the mid-1870s that TR started to use the signature “Thee Jr.” invoking his father’s nickname, “Thee,” but only to family members.

After TR’s father passed away in 1878, TR dropped the “Jr.” and signed simply “Thee.”

(TR also occasionally used other signatures like “Ted” and “Tedo,” the latter seems to appear in letters to his sister Corinne). As David McCullough wrote in Mornings on Horseback, “He seemed not to know what he should be called.”

A number of different contemporary sources suggest that TR first acquired the nickname “Teddy” in college. A book published in 1899 by American author and editor Perriton Maxwell contains a chapter entitled “An Anecdotal Portrait of Colonel Roosevelt” and notes, “Theodore Roosevelt’s popular nickname of ‘Teddy’ was first applied to him while a student at Harvard.”

The Handbook of the United States Political History for Readers and Students (1905) likewise confirms the origin of “Teddy” during TR’s college years. Orison Swett Marden adds that TR was a freshman when he first received his nickname.

TR’s own writings also suggest this origin date as well, with TR using “Teddy” as his signature in a few letters. However, he did so rarely—a mere 12 times in a set of nearly 300 letters between 1867 and 1885. The last instance occurred on July 1, 1883 in a letter to his sister Corinne—according to the Theodore Roosevelt Center.

THE RISE OF “TEDDY”

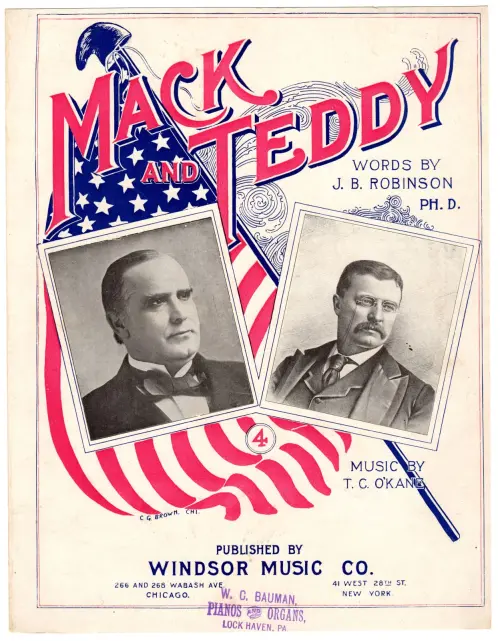

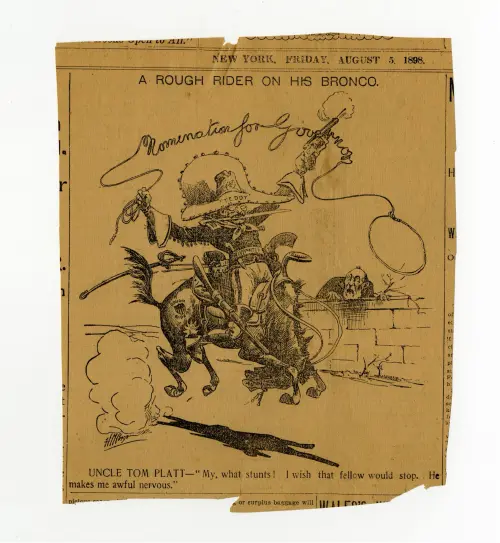

Though TR did not use the nickname much, newspapers were quite keen on it when reporting on Roosevelt’s rapid rise in political prominence.

In fact, newspapers started using “Teddy” just a few weeks after he was appointed a civil service commissioner by President Benjamin Harrison in May 1889.

As an article about TR published in the May 30, 1889 paper of The Inter Ocean states in the first sentence, “‘Teddy,’ otherwise Theodore, Roosevelt looks like his nickname.”

“Teddy” was more convenient, more approachable, and perhaps more amusing than his given name of Theodore for newspapers, especially those seeking to humanize or caricature him.

Even so, newspapers up until the Spanish-American War often used quotation marks around “Teddy,” indicating that it was a nickname. (Note the quotation marks in the 1889 article mentioned above, for example.)

Around the time of the Spanish-American War, Teddy started to become Roosevelt’s identity, as many newspapers started to forego the quotation marks.

In fact, before Roosevelt’s unit during the Spanish-American War became known as the Rough Riders, they were “Teddy’s Terrors.” (Roosevelt reportedly did not like the name.)

Some newspapers in the late 1890s worried that TR’s political prospects would be limited if he couldn’t disassociate himself from the nickname “Teddy.”

Ironically, the nickname “Teddy” almost seemed to make Roosevelt more popular, particularly after the creation of a now familiar toy—the teddy bear.

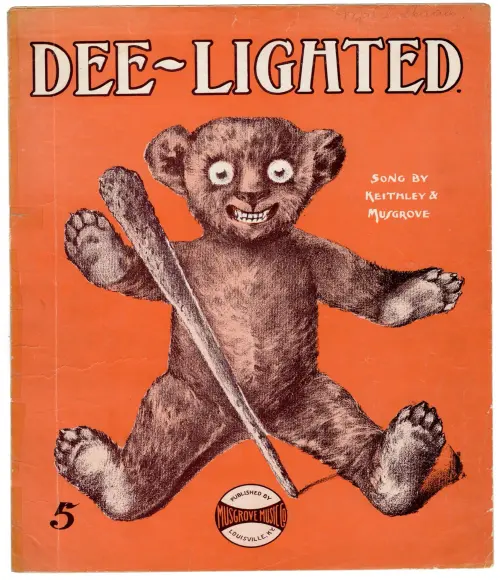

THE “TEDDY BEAR” THAT CEMENTED IT

What truly locked Roosevelt’s nickname into American consciousness was the “Teddy bear”—particularly since it was inspired by Roosevelt’s own action.

In 1902, while president, Roosevelt went on a hunting trip in Mississippi. Local guides, eager to ensure his success, captured a black bear and tied it to a tree for him to shoot.

Roosevelt, who prided himself on being a sportsman, refused to kill the helpless animal. News of the incident spread, and cartoonist Clifford Berryman immortalized the scene in a Washington Post cartoon titled “Drawing the line in Mississippi.”

Soon after, Jewish immigrants, Morris and Rose Michtom, Brooklyn candy shop owners, created a stuffed toy bear, branding it the “Teddy’s Bear.” The toy became a sensation, and the association between TR and the cuddly “teddy bear” became inescapable.

Clifford Berryman, who had helped encourage the sensation with his cartoon, featured one or more teddy bears in almost every single subsequent cartoon in which he highlighted Roosevelt.

Many others also started using the teddy bear as an association with TR—and the nickname of “Teddy” was permanently attached to him.

ROOSEVELT’S DISLIKE OF BEING CALLED “TEDDY”

There are divergent accounts regarding whether TR liked being called “Teddy” by the American public. On the one hand, the press reported on TR’s dislike of the name. For example, a Tammany Times article from May 22, 1903 noted TR’s dislike for the nickname: “‘Hello Teddy!’ yelled an irrepressible small boy to his face as Mr. Roosevelt emerged from the Yosemite [hiking with John Muir]. This hail is said to have met with a prompt Presidential veto.”

Similarly, an article in the October 23, 1907 edition of the Chicago Tribune observed, “A newspaper dispatch the other day attributed to President Roosevelt the statement that he liked to be called ‘Teddy’ by the American people because he regarded it as a term of endearment. The friends of the president in Washington doubt if he said anything of the kind.”

However, other sources suggest that he did like the nickname when used by the public. As Christian Fichthorne Reisner wrote in Roosevelt’s Religion (1922), “While on campaigns he was pleased by the shout ‘Teddy!’” Similarly, newspapers across the country reported on an incident in 1910 suggesting that TR had changed his stance on the nickname. While in Erie, Pennsylvania, a member of the crowd where TR was speaking shouted, “O, you Teddy bear!”

According to August 26, 1910 edition of The Boston Globe, “The ex-President looked around and smiled at the young man who dared to make so free with his name, but he didn’t resent it. Instead he turned to Congressman Bates and said loud enough so that quite a number of people could hear it: ‘I used to think that it lowered my dignity to have them call me Teddy—but now, don’t you know, I rather like it.’”

In either case, even if TR was known as “Teddy” politically, he did not use the name personally. For example, according to Reisner, “[N]o one ever thus addressed him personally [as Teddy]. Though he called a great many intimate friends by their first names, yet only when they had known him all their lives and were practically of the same age did they call him ‘Theodore.’”

Donald Richberg likewise writes in “Tents of the Mighty” (1929), “And somehow the chill-eyed Wilson inspired an awed devotion very different from the respectful but familiar enthusiasm around our magnetic ‘Teddy’ who, by the way, was never called ‘Teddy’ except by strangers!”

Finally, the August 1924 edition of The Current History Magazine notes, “Colonel Roosevelt [his preferred name after the presidency] never permitted himself to be called Teddy, despite a widespread impression to the contrary.”

And perhaps most importantly, TR’s daughter Alice Roosevelt Longworth stated, “Father didn’t like to be called Teddy.”

After childhood, TR did not have a nickname of choice to replace his childhood nickname of Teedie. As an adult, those close to him called him “Theodore,” and he preferred to be called “Colonel Roosevelt” by the public after he left the presidency.

FROM NICKNAME TO PUBLIC IDENTITY

Despite Roosevelt’s protests, the nickname endured. Political opponents used it to mock him, while supporters used it affectionately. Newspapers found it too catchy to abandon.

The “Teddy bear” craze, in particular, meant that children across the United States grew up hugging a reminder of Roosevelt. For them, “Teddy” was inseparable from the man who embodied adventure, vitality, and reform.

If anything, “Teddy” became an even more popular nickname as Roosevelt grew older. In the “Nicknames of Famous Personages” section of a 1912 encyclopedia, six of TR’s eleven nicknames contained some version of his famous nickname: “Teddy,” “Terrible Teddy,” “Teddy the First,” “Our Teddy,” “Toothful Teddy,” and “Teddy the Smiler.” Likewise, “Teddy the terrible” is included as a presidential nickname in the Oregon Teachers Monthly publication from 1915.

As one school journal in 1925 wrote, “No great American of modern times has more truly won his way to the heart of the average American than did Theodore Roosevelt. To earn a nickname ending in Y as he did, one must have the nation’s intimate affection as well as its respect and admiration.”

Teddy Roosevelt—not Theodore Roosevelt, TR, or even Colonel Roosevelt—had become a cultural icon, a larger-than-life character in American imagination.

THE ENDURING POWER OF “TEDDY”

Today, more Americans know Roosevelt as “Teddy” than as “TR” or “Theodore.” The teddy bear remains a fixture in nurseries not only across the country but across the world. Parks, schools, and even highways bear his formal name, but in popular culture, Teddy Roosevelt reigns.

In a way, his nickname has achieved something Roosevelt himself might not have realized: it has made him approachable. Children who would never study the intricacies of the Square Deal or the Roosevelt Corollary still know “Teddy” as the president who saved a bear. The nickname has humanized him for generations who might otherwise see him only as a stern face in history books.

Some might wonder: does it really matter what Roosevelt thought about the nickname? After all, the nickname has outlived him by more than a century. Noting his irritation helps us see the tension between how leaders want to be remembered and how the public chooses to remember them.

In the end, Roosevelt lost the battle over his name, but he gained something else: a place in American memory that is both formidable and endearing. The very tension between “Theodore” and “Teddy” is part of what keeps him fascinating—a man who was, on the one hand, a serious reformer and, on the other, an enduring cultural icon.