WHY IS THEODORE ROOSEVELT IMPORTANT?

Few figures in American history loom as large as Theodore Roosevelt. A man of boundless energy, sharp intellect, and indomitable will, Roosevelt’s life and presidency shaped the United States at a moment when the nation was defining its place on the world stage.

He was a soldier and an adventurer, a reformer and conservationist, a man who embodied both tradition and innovation. Roosevelt’s importance endures not only because of the title he held as America’s 26th president but also because of the actions he took and the values he lived by as president.

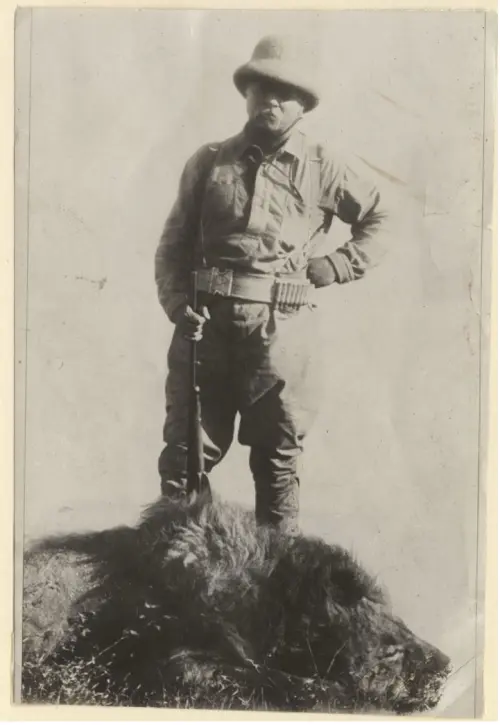

1. THE ROUGH RIDER

Roosevelt’s meteoric rise to national fame began on horseback in the hills of Cuba. After the sinking of the USS Maine on February 15, 1898, the United States declared war on Spain, believing the destruction of the Maine was a Spanish act of war.

Thirty-nine-year-old Theodore Roosevelt was eager to join the fight, especially because his father had not fought in the Civil War, instead hiring a substitute, to keep peace in the family with his Southern wife and in-laws.

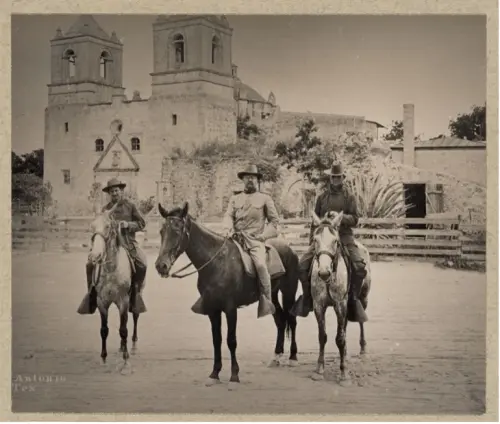

TR resigned his post as Assistant Secretary of the Navy to organize a volunteer cavalry regiment. He was second-in-command, serving under Colonel Leonard Wood. Officially known as the 1st U.S. Volunteer Cavalry, the unit became famous under a more colorful name: the Rough Riders.

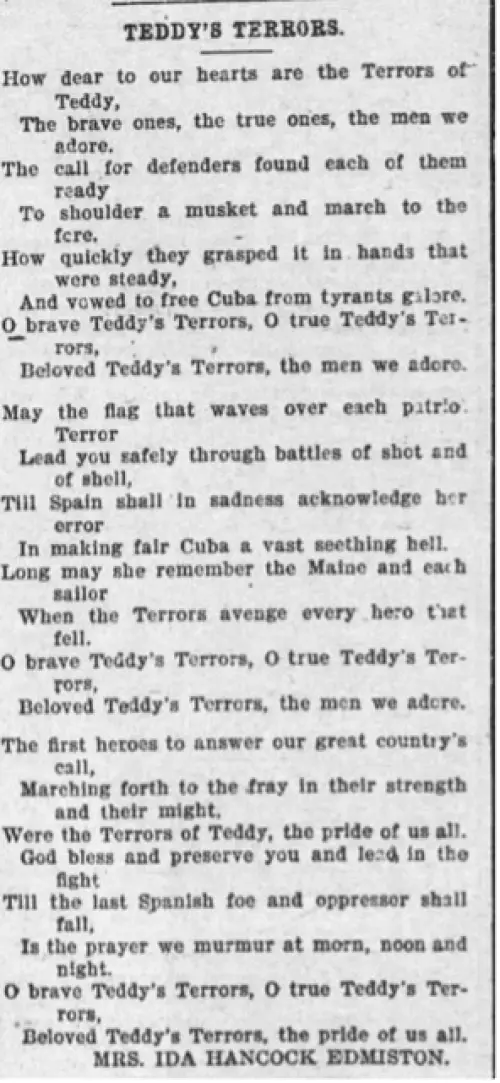

Other names that the newspapers initially coined for the regiment included Teddy’s Terrors, Teddy’s Texas Tarantulas, Teddy’s Gilded Gang, Teddy’s Cowboy Contingent, Teddy’s Riotous Rounders, and Roosevelt’s Rough ’Uns.

Donning the official uniform of the unit of a slouch hat, blue flannel shirt, brown trousers and leggings, and polka-dot bandanas, 1,060 men served as Rough Riders. Composed of cowboys from the West, Ivy League athletes, Native Americans, and adventurers of all stripes, the Rough Riders reflected Roosevelt’s own belief in rugged individualism and national unity. Roosevelt himself recruited many of them, and his charisma quickly bound the eclectic unit together.

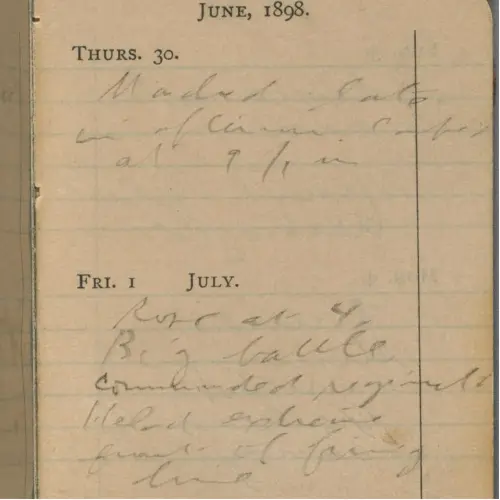

The Rough Riders’ most famous moment came on July 1, 1898, at the Battle of San Juan Hill Heights. Under a punishing rain of Spanish fire, confusion rippled through the American lines. Orders were unclear, regular Army officers hesitated, and men faltered in the open field.

Sensing disaster, Roosevelt refused to wait. He mounted his horse, Little Texas, and rode to the front, seizing command. Exposed to the storm of bullets, he rallied his men with a shout and drove them forward up Kettle Hill.

Step by step, the regiment followed his example. By day’s end, eighty-nine Rough Riders had fallen, but their charge—pulled into motion by Roosevelt’s fearless leadership—secured the heights of San Juan Hill and Kettle Hill.

As TR wrote in his diary on July 1, “Rose at 4. Big battle. Commanded regiment. Held extreme front of firing line.” This day—and the following days in battle—TR would remember the rest of his life, calling them “great days” and his “crowded hour.”

TR and the Rough Riders returned to the States to a huge crowd, and Roosevelt and his unit became national heroes, symbolizing American grit, unity, and a readiness to face danger. His popularity brought him to the attention of New York’s Republican party boss, Thomas C. Platt, who offered to put Roosevelt forward as the Republican candidate for New York’s gubernatorial election in November 1898.

With Roosevelt’s win in November, he began his rapid rise in politics from New York governor to vice president and finally to president. But the public never forgot TR the Rough Rider, as illusions to the Rough Riders would appear in all sorts of public memorabilia from pins to sheet music—and even in cocktails.

As Rough Rider, Roosevelt demonstrated his courage, his willingness to lead by example, and his belief in the commonality of all Americans—something that people continue to admire about Roosevelt to this day.

2. THE CHAMPION FOR SAFER FOOD

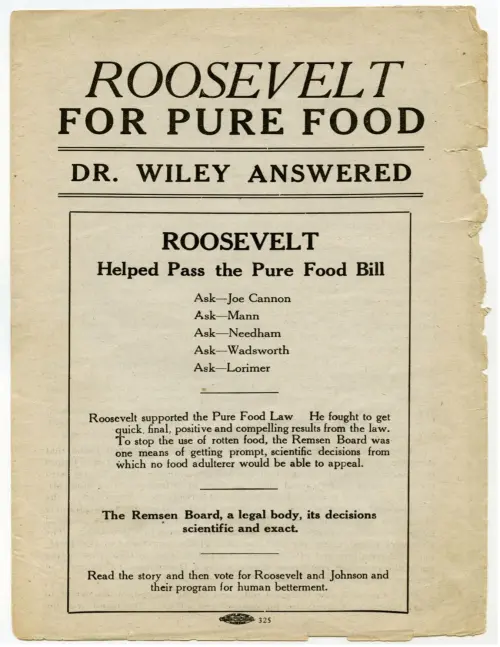

After he became president, Roosevelt’s accomplishments shifted from the battlefield to the political arena. One of his most lasting domestic achievements was the passage of the Pure Food and Drug Act and the Meat Inspection Act in 1906.

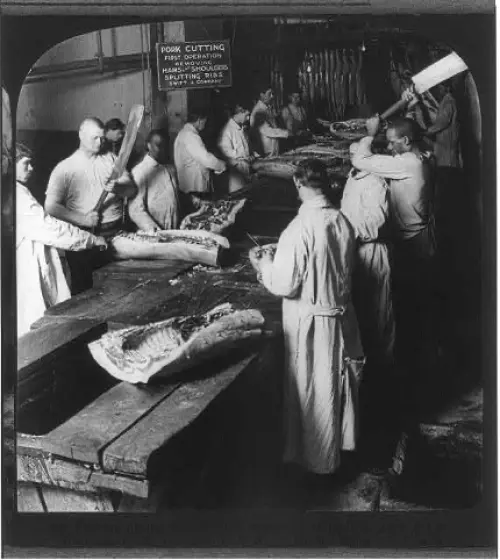

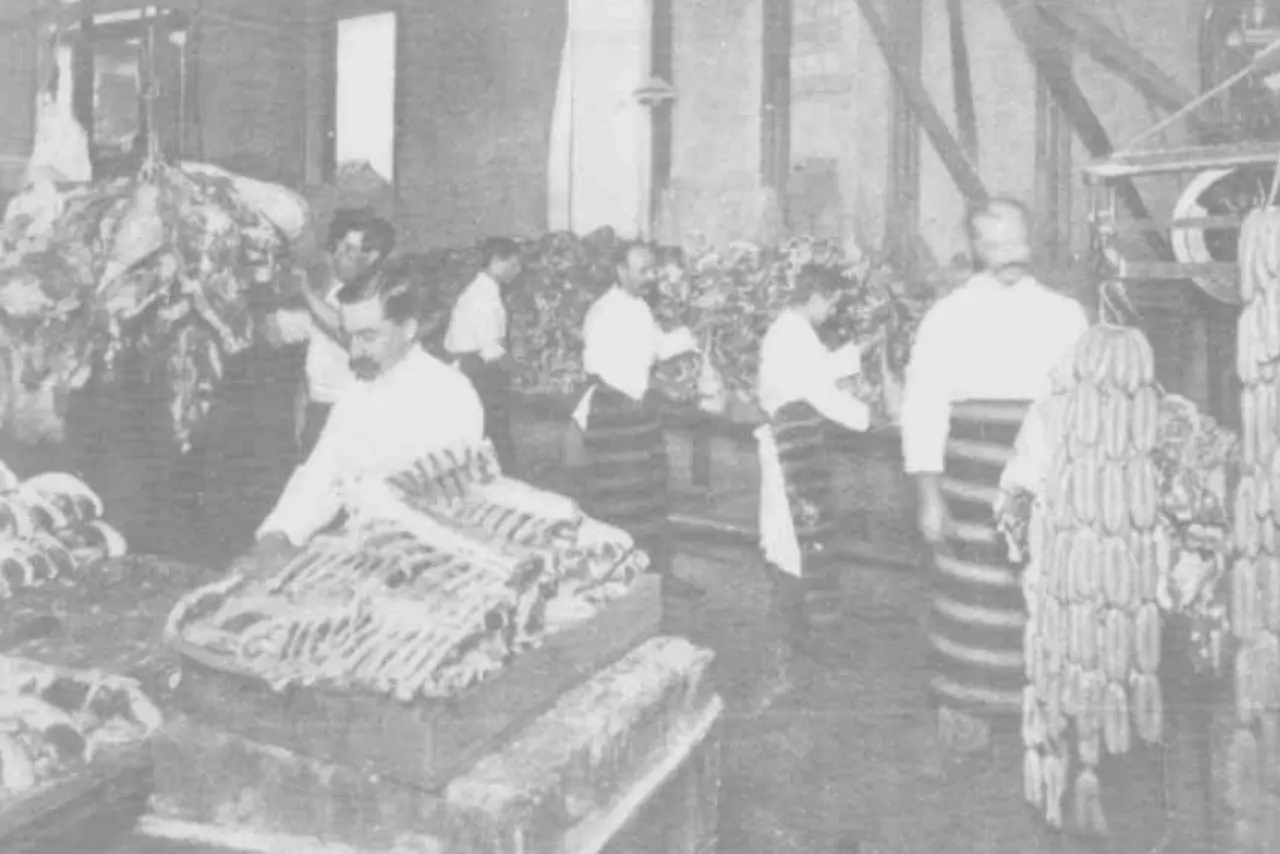

At the dawn of the 20th century, America’s rapidly industrializing food system was riddled with abuses. Meatpacking plants were unsanitary, medicines often contained dangerous ingredients, and misleading labels tricked consumers.

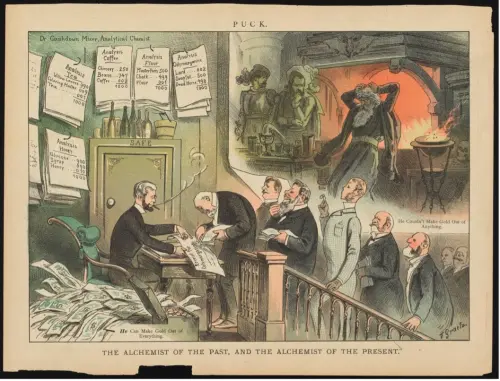

Moreover, there were no federal regulations on food safety, meaning that companies could make a fast profit by adulterating—or contaminating—foods with other ingredients to improve their color or decrease the cost to make them.

At the time of Theodore Roosevelt’s presidency, some of the most unsafe foods were meats and chocolate. The latter often contained all sorts of dangerous ingredients, including brick dust, copper sulfate, and powdered tin.

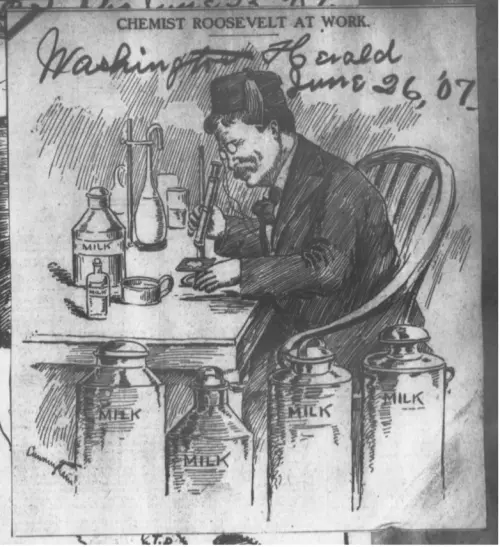

The efforts of people like Dr. Harvey Washington Wiley, Chief Chemist of the Bureau of Chemistry in the United States Department of Agriculture, and muckraking journalists like Upton Sinclair began to expose the dangers the American public faced in their foods.

In particular, public outrage swelled after the publication of Sinclair’s book, The Jungle, a novel which vividly described the filthy conditions in Chicago’s stockyards, on February 26, 1906. Sometime in the spring of 1906, Roosevelt himself read The Jungle.

Even though Roosevelt and Sinclair did not see quite eye-to-eye (TR did not care for the socialism that ran through The Jungle, for example), the president jumped into action to investigate the claims made in the book about the meatpacking industry.

When several government investigations revealed the accuracy of Sinclair’s claims, Roosevelt began to work with Congress to pass more stringent regulations on meat handling for the safety of the American consumer.

On June 30, 1906—about four months after the publication of The Jungle, Roosevelt signed the Meat Inspection Act and the Pure Food and Drug Act into law. The Pure Food and Drug Act established the first federal regulations for food and medicine, banning mislabeling and harmful additives. It also laid the groundwork for what would become the Food and Drug Administration.

Roosevelt considered the passage of the Pure Food and Drug Act as one of the most important accomplishments of his presidency. As he said in his last message to Congress on January 22, 1909, “The enactment of a pure food law was a recognition of the fact that the public welfare outweighs the right to private gain, and that no man may poison the people for his private profit.”

Roosevelt’s insistence on protecting ordinary citizens from powerful interests revealed his deep commitment to fairness and justice. While more food safety laws have been passed since 1906, these two laws are still recognized today for initiating a change in food safety for Americans. In many ways, modern consumer safety laws like grades of meat trace their roots back to TR’s advocacy in 1906.

3. THE FATHER OF CONSERVATION

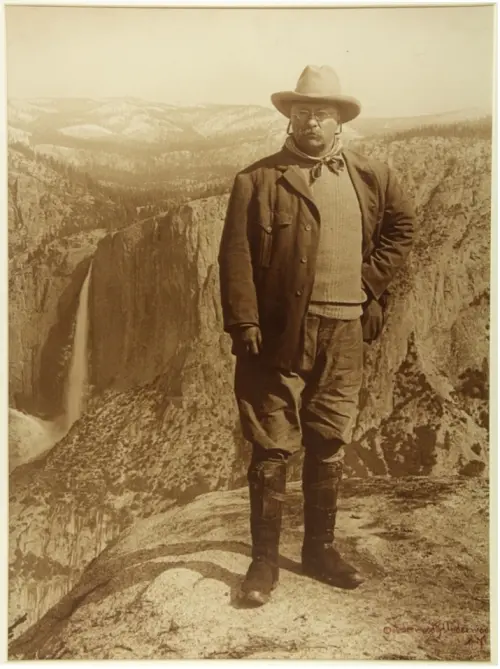

Perhaps no achievement defines Roosevelt more than his role as the nation’s first great conservation president. At the turn of the century, vast tracts of America’s wilderness were being logged, mined, and destroyed without restraint.

Roosevelt saw in this unchecked exploitation both a moral failing and a national danger. “The nation behaves well,” he wrote, “if it treats the natural resources as assets which it must turn over to the next generation increased, and not impaired, in value . . .”

Inspired by his time in the raw beauty of North Dakota’s Badlands in the 1880s, Roosevelt brought his passion for nature to the presidency and acted with unprecedented vigor. He oversaw the creation of 4 game preserves, 18 national monuments, 51 wildlife refuges, and 150 national forests. During his presidency, Congress also established 5 national parks.

Although the National Park Service was not created until 1916, Roosevelt’s work helped pave the way for this agency. All told, TR assisted in the establishment of approximately 230 million acres under federal protection—an area equivalent to the entire Eastern Seaboard from Maine to Florida.

For Roosevelt, conservation was not about locking away land from human use. It was about balance: ensuring forests were managed sustainably, rivers preserved for future energy needs, and wildlife protected for the enjoyment of generations to come.

Roosevelt was not president when Yellowstone became our first national park—that happened under Ulysses S. Grant. Still, he is closely linked with many of America’s national parks. As president, he visited Yellowstone, underscoring its importance. And while the Grand Canyon would not be designated a national park until 1919, Roosevelt ensured its protection earlier by declaring it a national monument.

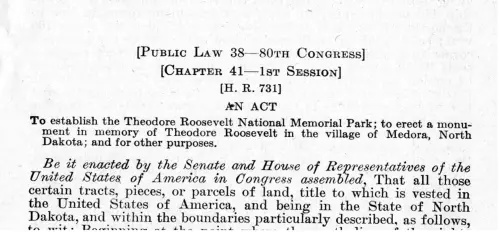

In recognition of Roosevelt’s tireless efforts to protect public lands and in honor of his time in North Dakota, Congress established Theodore Roosevelt National Memorial Park on April 25, 1947. In 1978, the park’s designation became Theodore Roosevelt National Park.

Roosevelt’s pragmatic yet visionary approach set the foundation for America’s modern conservation movement. Today, hikers in Yosemite, birdwatchers at Pelican Island, and campers in countless national forests benefit from his foresight.

All that said, although Theodore Roosevelt is justifiably lauded for his support of conservation and preservation of public lands, it’s important to acknowledge that this sometimes came at a cost to the Native people who had called those areas home for thousands of years and that it’s only been recently that the federal government has started to address these issues.

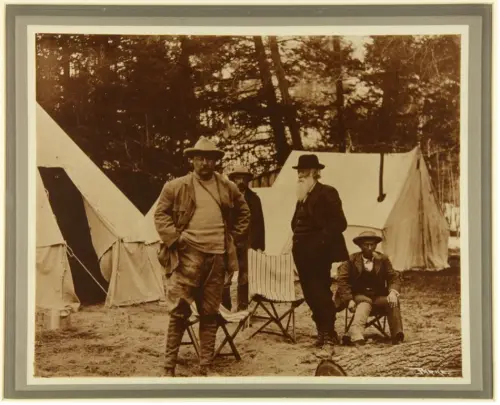

4. THE HUNTER-CONSERVATIONIST

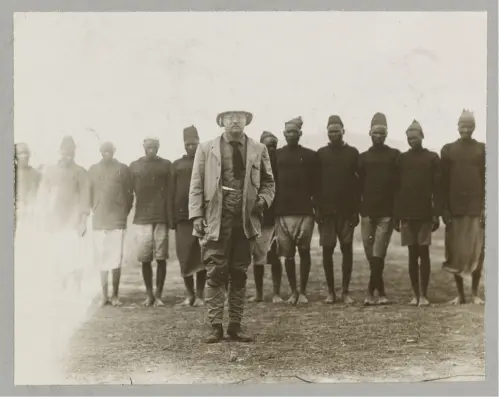

Roosevelt’s passion for the natural world did not end with his presidency. In 1909, shortly after leaving office, he embarked on the Smithsonian-Roosevelt African Expedition. Accompanied by his son Kermit, scientists, and guides, he spent nearly a year traversing British East Africa (modern-day Kenya and Uganda), the Congo, and Sudan.

The expedition party consisted of Roosevelt, 19-year-old Kermit, three American naturalists, Edgar Alexander Mearns, Edmund Heller, and J. Alden Loring, an Australian sharpshooter, and hundreds of porters, gunbearers, guards, local guides, and hunters.

Although sometimes seen as a trophy-hunting safari with wanton killing of animals, the Smithsonian-Roosevelt Expedition was no such thing. Along the way, the party collected roughly 11,000 animal specimens—everything from insects to elephants—for the Smithsonian Institution.

While some critics decried the scale of the hunt, Roosevelt saw the endeavor as scientific and educational, intended to expand public understanding of Africa’s ecosystems. TR killed 296 animals himself, and his son Kermit killed 216. As Smithsonian mammalogist Darrin Lunde noted, “[T]hat was not even a tenth of what they might have killed had they been so inclined.”

This expedition not only reinforced TR’s identity as a man of action but also highlighted his belief that science and adventure could serve the public good. By bringing Africa’s wildlife back to the United States, he hoped to foster curiosity and respect for the natural world.

And it has to this day. The specimens Roosevelt and others on the expedition collected are still used by scientists today for research, such as the 2015 “Roosevelt Resurvey” expedition and efforts to restore the ecosystem at the Ajai Reserve to that which existed during Roosevelt’s time.

5. THE TECHNOLOGICAL PROGRESSIVE

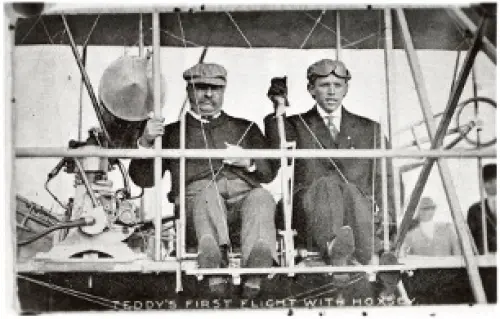

Though Roosevelt loved the wilderness, he was no enemy of modern progress. On the contrary, he embraced new technologies with gusto. He was the first president to ride in an automobile while in office, the first to fly in an airplane (watch a video of the flight here!), and the first to communicate widely via telephone as well as the first to have it installed in his home, Sagamore Hill. He invited inventors and engineers to the White House, eager to understand the machines that were transforming society.

Theodore Roosevelt embraced new technology not just out of curiosity, but because it symbolized American progress and national strength. Roosevelt saw technology as a tool for improving lives from expanding transportation networks to bolstering the military.

That said, Roosevelt also acknowledged the growing pains that came with technology, writing in a 1905 letter to Charles Hughes that “motor cars are a trial” and “ultimately we will get them into their proper place in the scheme of nature . . . but just at present I regard them as distinct additions to the discomfort of living.”

But he knew society was changing—and Americans, especially leaders like the president, needed to adapt accordingly. By riding in automobiles, flying in airplanes, and championing modern warships, he showed that the United States was bold, innovative, and ready to compete with older world powers. For Roosevelt, technology was both a practical tool and a patriotic emblem of America’s rise in the 20th century.

ROOSEVELT’S ENDURING IMPORTANCE

Theodore Roosevelt’s life was as varied as it was consequential. As a Rough Rider, he demonstrated courage; as a reformer, he championed fairness; as a conservationist, he preserved America’s natural heritage; as an explorer and naturalist, he pursued scientific knowledge for the public good; and as a modernizer, he welcomed the future with open arms.

His importance lies not only in the specific policies he enacted or the battles he fought but in the spirit he embodied—a restless energy that pushed the nation to be bolder, braver, and better. Roosevelt himself wrote in his Autobiography that Squire Bill Widener’s philosophy summed up an individual’s goal in life: “Do what you can, with what you’ve got, where you are.” It was advice he lived by, and one that still resonates more than a century later.

In remembering Theodore Roosevelt, we see a man who believed that leadership required action, that progress demanded courage, and that the future belonged to those willing to meet it head-on. That is why Theodore Roosevelt still matters.