WHY IS THEODORE ROOSEVELT ON MOUNT RUSHMORE?

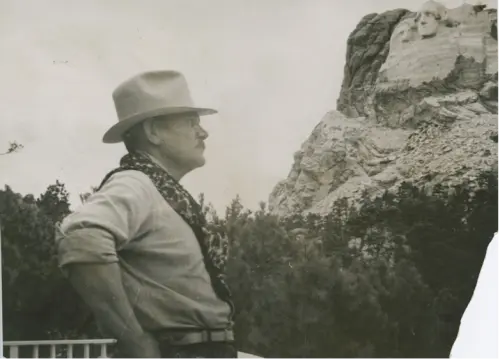

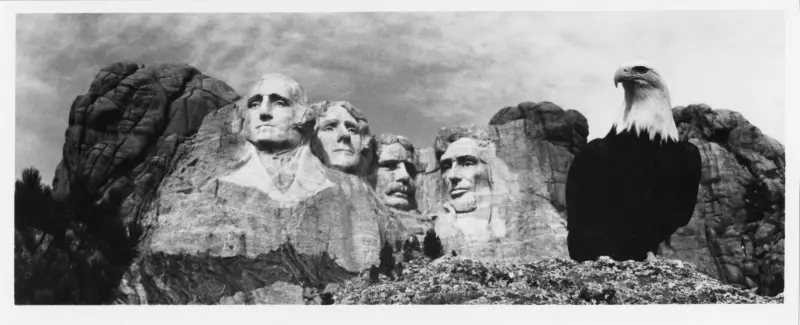

High in the granite face of South Dakota’s Black Hills, four giant visages—George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Abraham Lincoln, and Theodore Roosevelt—stare across the horizon. Mount Rushmore, one of America’s most iconic monuments, was carved between 1927 and 1941 to honor the country’s founding, growth, preservation, and development.

Each face was chosen to represent a defining era in American history, and Theodore Roosevelt’s inclusion symbolizes the nation’s rapid expansion, modern progress, and the energetic spirit that drove the United States into the 20th century.

THE VISION FOR MOUNT RUSHMORE

The idea for Mount Rushmore originated in the 1920s with South Dakota historian Doane Robinson, who wanted a colossal sculpture to attract visitors to his state. He envisioned western heroes such as Merriwether Lewis and William Clark or Buffalo Bill Cody carved into the towering granite spires of the Black Hills.

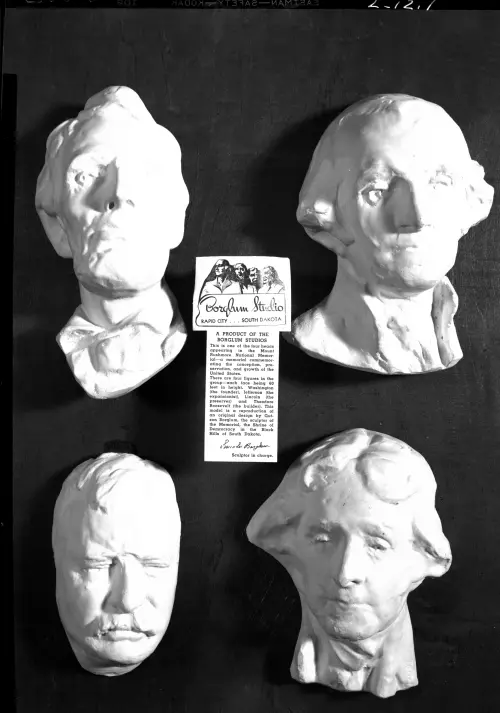

In 1924, he invited sculptor Gutzon Borglum—already known for his work on Stone Mountain in Georgia—to lead the project. Borglum had a grander vision: rather than regional heroes, he proposed a national shrine celebrating America’s ideals and endurance.

Borglum selected Mount Rushmore—named for New York lawyer Charles E. Rushmore—for its sturdy granite and southern exposure, which ensured the figures would be bathed in sunlight. (Before it became known as Mount Rushmore, the Lakota called it Tȟuŋkášila Šákpe or “Six Grandfathers.”)

Initially, the carving was also going to have an inscription called the Entablature—shaped like the Louisiana Purchase and featuring significant dates in America’s 150 years. But due to issues in the rock and concerns about being able to read the writing, the inscription was included in a room behind the sculpture.

Borglum chose the four presidents to tell the story of the American nation in monumental form carefully. Washington would represent the founding of the republic, Jefferson the expansion of democracy through the Louisiana Purchase, Lincoln the preservation of the Union, and Roosevelt the rise of the United States as a modern global power.

Work began officially on October 4, 1927, shortly after President Calvin Coolidge dedicated the project with thousands in attendance on August 10, 1927, stating, “The union of these four Presidents carved on the face of the everlasting hills of South Dakota will constitute a distinctly national monument. It will be decidedly American in its conception, in its magnitude, in its meaning and altogether worthy of our Country.”

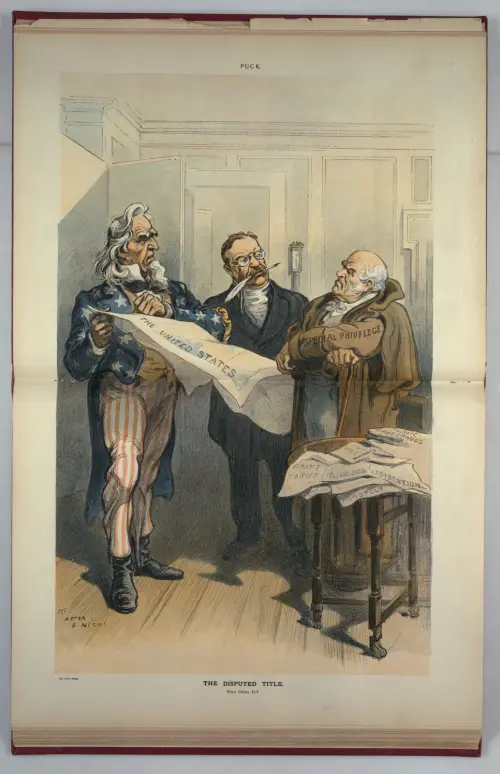

ROOSEVELT’S SYMBOLISM: THE AGE OF EXPANSION AND REFORM

The inclusion of Theodore Roosevelt was not merely symbolic; it was deeply personal for Borglum. The sculptor admired Roosevelt’s vigor and his belief in national greatness. Borglum even campaigned for him during the 1912 presidential election.

As Borglum saw it, Roosevelt embodied the dynamism of the new century—an outdoorsman, reformer, soldier, and statesman who viewed government as a force for moral and social improvement. Borglum saw him as the bridge between Lincoln’s America and the industrial, international United States that emerged after 1900.

Roosevelt’s legacy fit neatly into Borglum’s four-part narrative of American development. His presidency (1901–1909) marked a turning point when the U.S. government began regulating big business, protecting natural resources, and projecting power abroad. His work as a trustbuster, conservationist, and champion of the “Square Deal” represented the country’s maturity—a confident, reform-minded nation ready to lead the world.

The youngest president in U.S. history, Roosevelt pushed to curb corporate monopolies, secure fair treatment for workers, and ensure that natural wonders would be preserved for future generations. He oversaw the creation of five national parks established by Congress during his presidency, established 18 national monuments, and set aside roughly 230 million acres for public conservation—earning him the nickname, “The Conservation President.”

Equally important, Roosevelt transformed the United States into a world power. He oversaw construction of the Panama Canal, which linked the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, and negotiated peace in the Russo-Japanese War, for which he won the 1906 Nobel Peace Prize—the first American to do so. His famous foreign policy phrase, “Speak softly and carry a big stick,” summarized his belief that strength and diplomacy could coexist.

For Borglum, these qualities made Roosevelt the ideal symbol of the nation’s emergence on the world stage. Just as Jefferson had expanded America’s borders westward, Roosevelt had expanded its influence abroad.

CARVING THE MOUNTAIN

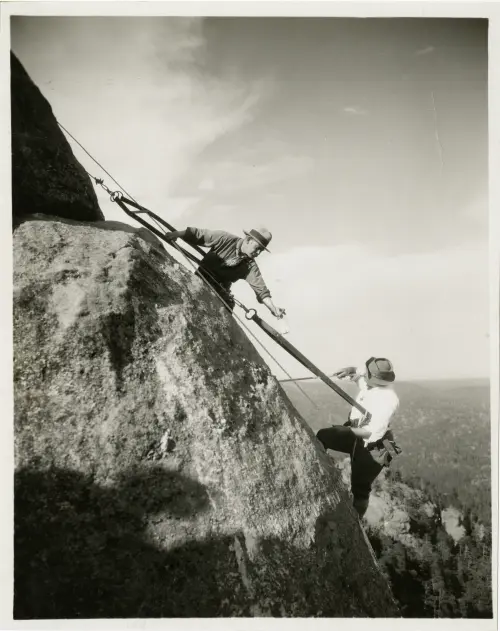

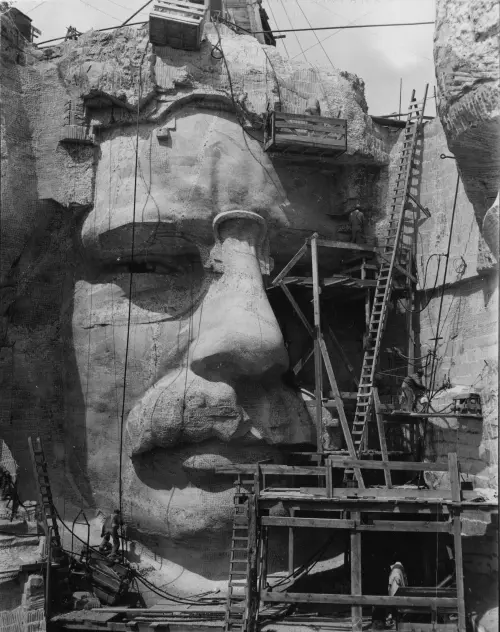

Transforming Borglum’s vision into reality was a feat of engineering and endurance. Workers used dynamite to remove nearly 450,000 tons of rock, followed by precise drilling and chiseling to form the faces.

Around 400 men and women—carvers, drillers, blacksmiths, and more—labored on the mountain with wages ranging from 35 cents to $1.50 per hour, or roughly $8.00 to $35.00 an hour today. Despite the dangerous conditions, no one was killed during construction, an extraordinary fact given the scale of the project.

Washington’s face was completed first, dedicated on July 4, 1930, followed by Jefferson’s on August 10, 1936. Lincoln’s likeness emerged from the granite, dedicated on September 17, 1937. Roosevelt’s head, set slightly deeper into the mountain between Lincoln and Jefferson, was the most difficult to carve because of the rock’s uneven surface.

His glasses, moustache, and deeply set eyes posed additional challenges for the sculptors. Nevertheless, by 1939 his face was largely finished, capturing the characteristic expression of determined vitality that made Roosevelt so memorable. It was officially dedicated on July 2 of that year.

THE LEGACY OF MOUNT RUSHMORE

The entire monument was declared complete on October 31, 1941, just weeks before the United States entered World War II. Although Borglum had originally planned for full figures from head to waist, funding shortages and his own death earlier that year forced the project to end with the four colossal faces alone. His son, Lincoln, had taken over, but wasn’t able to complete the full vision his father had.

When Mount Rushmore was completed, it stood as a statement of democratic endurance during a time of global uncertainty. Europe was engulfed in war, and the United States was weeks away from the attack on Pearl Harbor and the American entrance into the war. The monument reminded Americans of their shared past and the leaders who had guided them through moments of trial and transformation.

Over the decades, Mount Rushmore has become a defining American image, visited by millions each year. While it has also prompted debate—particularly over its location in the Black Hills, a region sacred to the Lakota Sioux—it remains a powerful symbol of national identity. The four presidents carved into the granite represent not perfection, but progress, the ongoing effort to live up to the country’s founding ideals.

Among them, Theodore Roosevelt captures a uniquely American spirit: energetic, pragmatic, and forward-looking. He represents the courage to confront new frontiers—whether geographic, industrial, or moral—and to do so with confidence and faith in the nation’s potential.