WHY WAS THEODORE ROOSEVELT SHOT?

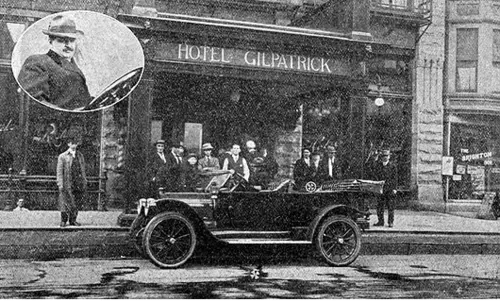

It’s the evening of Monday, October 14, 1912, three weeks from election day. Former president Theodore Roosevelt is on the campaign trail in Wisconsin. He has just eaten dinner at the Hotel Gilpatrick in Milwaukee and is about to depart for the Milwaukee Auditorium where he is going to speak. Upon exiting the hotel, he crosses the walk and steps into the waiting automobile.

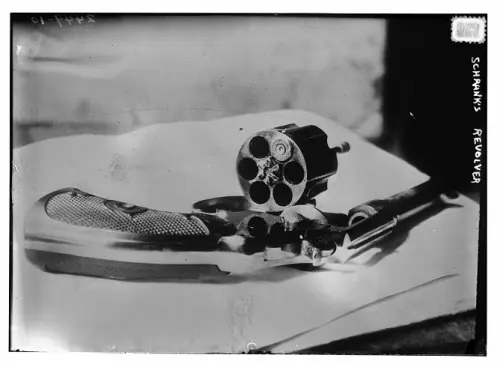

At first, TR sits down in the car but then stands when an enthusiastic crowd greets him and raises his hat in a salute. Boom! A man pressed close to the vehicle—within four or five feet—fires a single shot from a Colt revolver ten minutes past eight o’clock that evening. The bullet—a .38 shot from a .44 frame—strikes Roosevelt in the chest and pierces his overcoat, glasses case, and the thick manuscript of his 50-page speech before lodging in his chest.

Some called for the would-be assassin, John Flammang Schrank, to be killed immediately, but, as in the case of the boat thieves in 1886, Roosevelt insisted in fair justice: “Take charge of him, and see that there is no violence done to him.”

The other people in the automobile urged Roosevelt to go to the hospital, but TR refused, saying, “This may be my last talk in this cause to our people, and while I am good I am going to drive to the hall and deliver my speech.”

THE BULLET AND THE BULL MOOSE

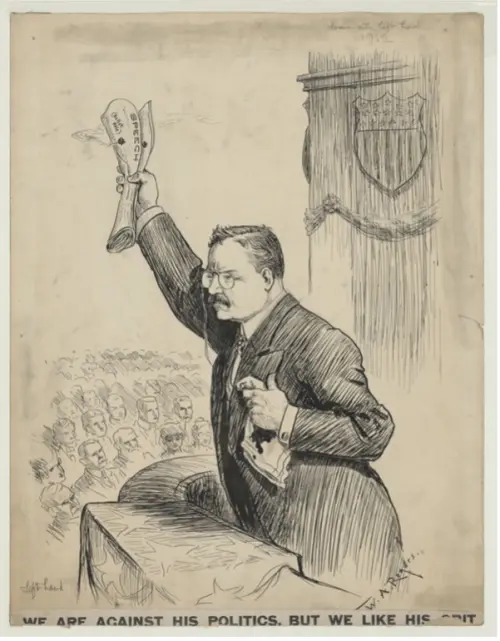

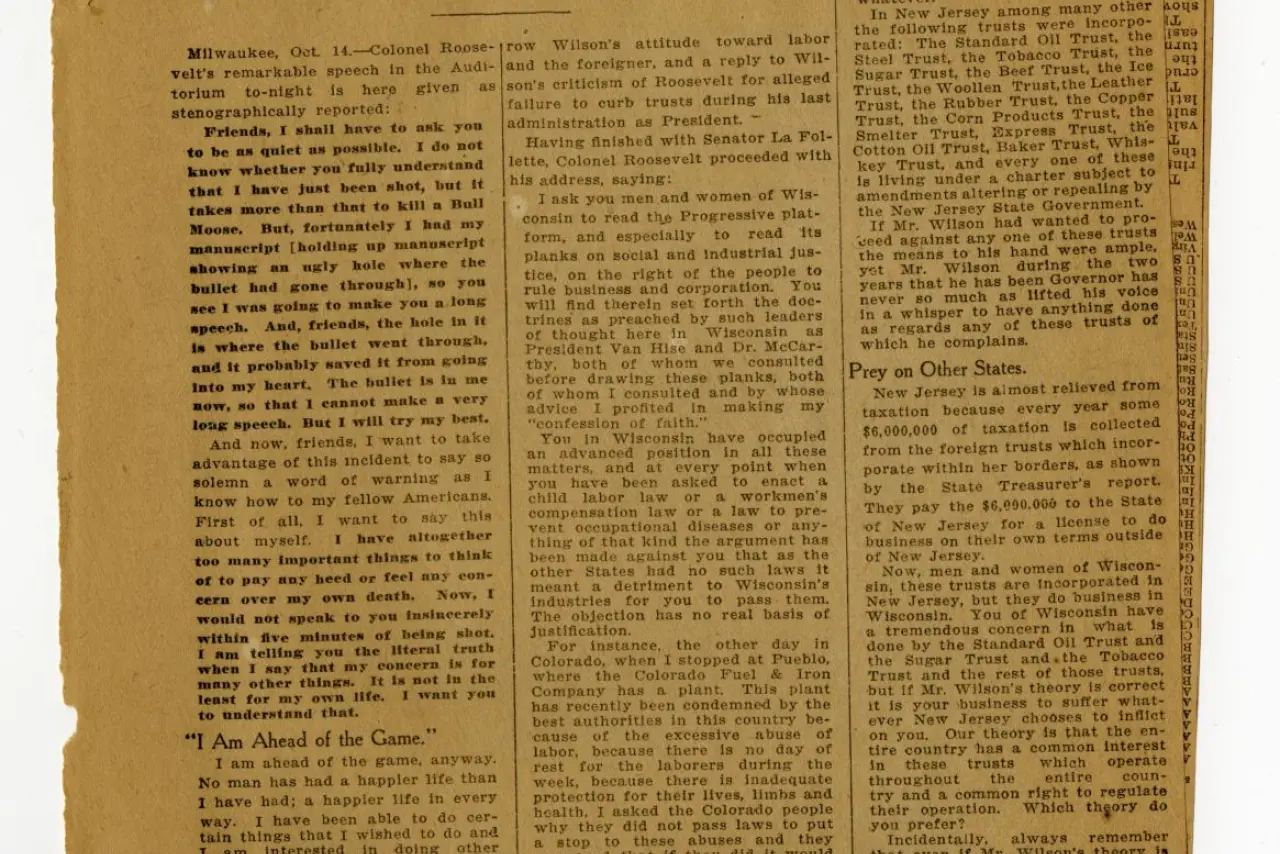

With blood seeping through his shirt, Roosevelt proceeded to the Milwaukee Auditorium and was introduced by Henry F. Cochems, who had been with TR in the car when he was shot. Cochem informed the audience that there had been an attempt on TR’s life. Someone in the crowd suggested it was fake, but Roosevelt opened his vest and showed his wound to the stunned audience of 9,000 people.

And then TR began his speech: “Friends, I shall ask you to be as quiet as possible. I don’t know whether you fully understand that I have just been shot; but it takes more than that to kill a Bull Moose.” He then spoke for nearly an hour-and-a-half before finally allowing doctors to examine him.

The dramatic moment became one of the most extraordinary episodes in American political history. Yet the story of why Roosevelt was shot goes deeper than a single act of violence—it reflects the tensions of a nation divided by politics, the volatility of personal obsession, and the risks of Roosevelt’s own relentless drive to run for a third term.

A FRACTURED POLITICAL LANDSCAPE

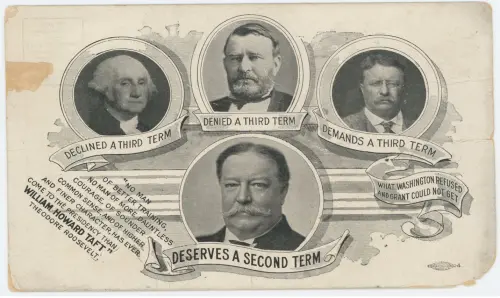

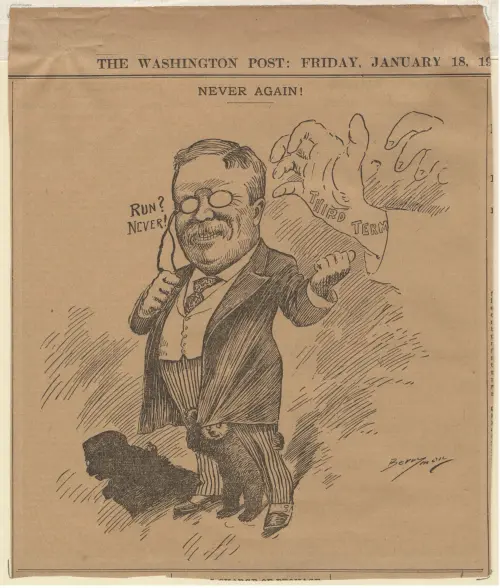

The 1912 presidential election was bitterly contested. In June 1912, Republican party bosses opted to nominate William Howard Taft, the incumbent president, instead of Roosevelt at the Republican National Convention. In response, TR broke away from the Republican Party to form his own party—the Progressive Party, colloquially known as the Bull Moose Party.

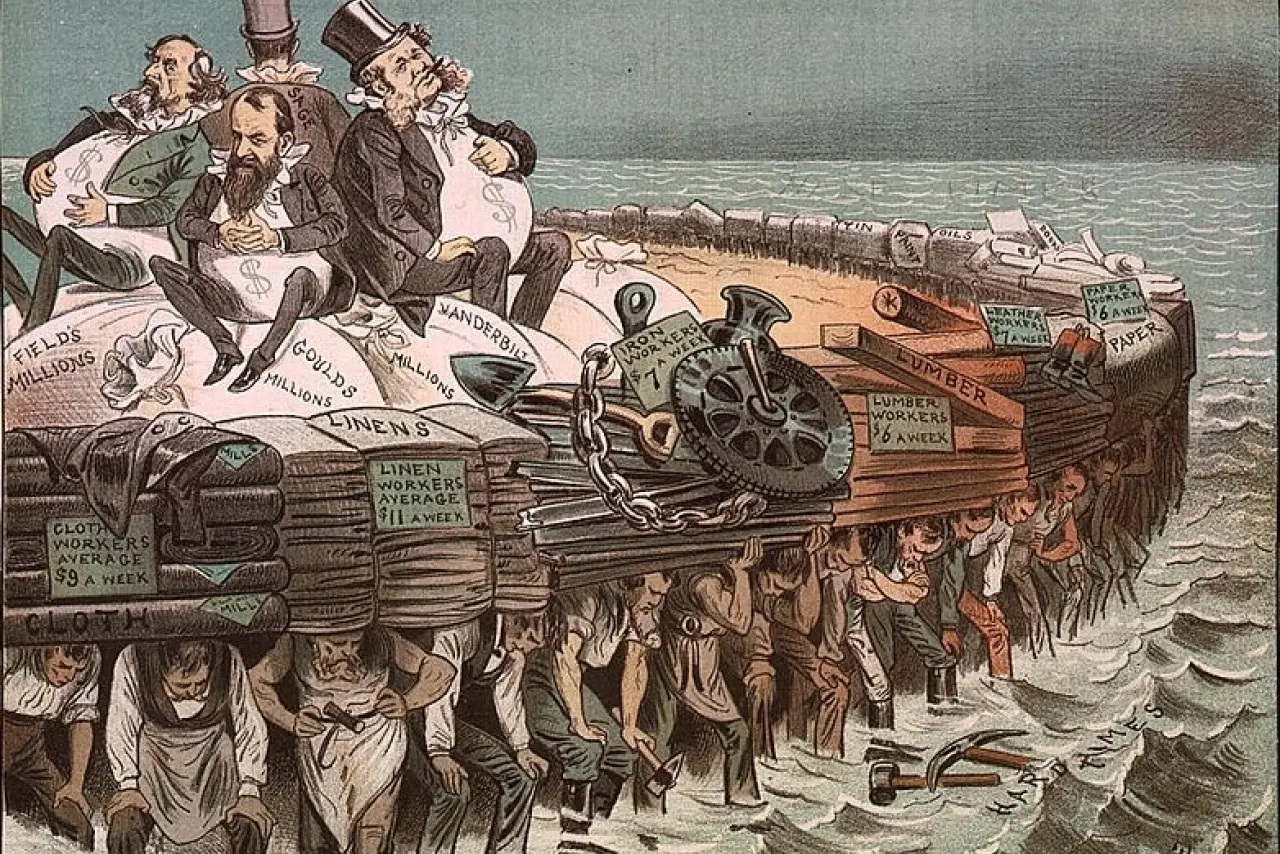

Under the Progressive umbrella, he campaigned on an ambitious reform platform: women’s suffrage, direct democracy through initiatives and referenda, limits on corporate power, and social insurance for workers. His energy and charisma electrified supporters but deeply angered traditional Republicans who viewed him as a traitor dividing the conservative vote.

The Democratic nominee, Woodrow Wilson, had his own reform program, similar to Roosevelt’s. The result was a political three-way collision: Wilson and Roosevelt appealing to reform-minded voters, the Progressive Party attracting those who supported TR or who appreciated his own personal charisma, with Taft holding the Republican establishment.

THE MIND OF AN ASSASSIN

John Flammang Schrank, the man who pulled the trigger, was a 36-year-old Bavarian immigrant and former saloonkeeper. He lived in New York when Roosevelt was police commissioner and reported to police that TR had closed his family’s liquor business. Schrank had not been married and had lost his sweetheart, Elsie Ziegler, in the General Slocum steamboat disaster. He was intelligent but eccentric, prone to religious delusions and intense loneliness.

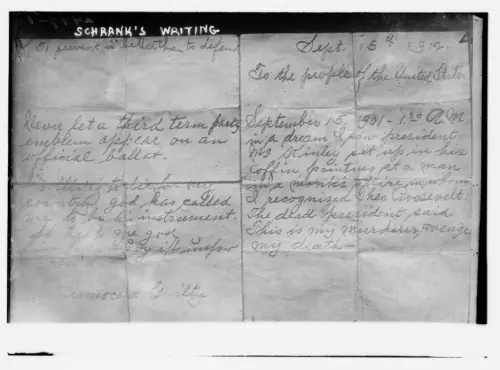

In the months before the shooting, Schrank became obsessed with Roosevelt’s return to politics. He claimed to have experienced a dream in which the ghost of President William McKinley—assassinated in 1901—appeared to him, accusing Roosevelt of being responsible for his death. According to Schrank, the apparition commanded him to avenge McKinley’s spirit by killing Roosevelt before he could seize power again.

This strange mixture of personal instability and symbolic vengeance fused with the heated rhetoric of the campaign. Schrank followed Roosevelt’s whistle-stop tour across several states from Alabama to Indiana, sleeping in hotels under the name of “Walter Ross.” For weeks he stalked his target, waiting for the right moment. When Roosevelt arrived in Milwaukee on October 14, Schrank finally acted.

Nearly a month after the assassination attempt, Schrank appeared in municipal court on November 13, 1912. His appearance was quite different than when he shot Roosevelt. He was clean shaven and dressed in a pressed suit. When asked if he intended to kill TR, he stated, “I intended to kill Theodore Roosevelt, the third termer.”

Nine days later, five psychiatrists declared Schrank legally insane. Roosevelt himself didn’t agree with this assessment, stating in a December 1912 letter, “He was not really a madman at all; he was a man of the same disordered brain which most criminals, and a great many non criminals [sic], have.”

Schrank spent the rest of his life—more than three decades—in a Wisconsin asylum in Oshkosh, Wisconsin before his death in 1943 when his body was donated to the local medical school for dissection. Yet the bizarre reasoning behind his act reflects a larger anxiety in early twentieth-century America: fear that powerful personalities like Roosevelt might dominate democracy itself.

ROOSEVELT’S COURAGEOUS RESPONSE

Roosevelt’s behavior the night that he was shot only reinforced his legend as a larger-than-life figure. After being struck, he checked to see if he was bleeding from the month to determine whether a lung had been punctured. Seeing none, he judged himself fit to continue in his activities. The folded speech and eyeglass case had slowed the bullet’s velocity, likely saving his life.

Roosevelt began his 80-minute speech showing the audience his manuscript with the bullet hole. He declared, “The bullet is in me now, so that I cannot make a very long speech, but I will try my best.” His audience sat in stunned silence as he worked his way through his remarks, at times visibly trembling but defiant. During the address, his voice weakened, and his aides begged him to stop, but TR refused until he was done.

As TR wrote later in a letter to his son Kermit, “Well, this campaign proved as exciting and as dangerous as any of our African hunts . . . .” TR added that he always had known since becoming president that he could be shot and “had always determined that if I was shot when I was about to make a speech or anything of the kind I should go on with the speech . . .”

After the speech concluded, TR walked out on his own to the automobile waiting to take him to Johnston Emergency Hospital in Milwaukee. There Roosevelt’s doctor, Scurry L. Terrell, and two doctors from Milwaukee discovered the bullet lodged in his chest wall near the fourth rib on his right side. He was then taken on a special 12:30 train to Chicago where he arrived at Mercy Hospital around 3 a.m.

The doctors, including Dr. Terrell, decided not to remove the bullet, as surgery might be more dangerous than leaving it in place. Roosevelt carried the bullet inside him for the rest of his life—a literal reminder of the campaign’s violence and of his own resilience.

A GLIMPSE OF HOPE FOR TR’S CAMPAIGN

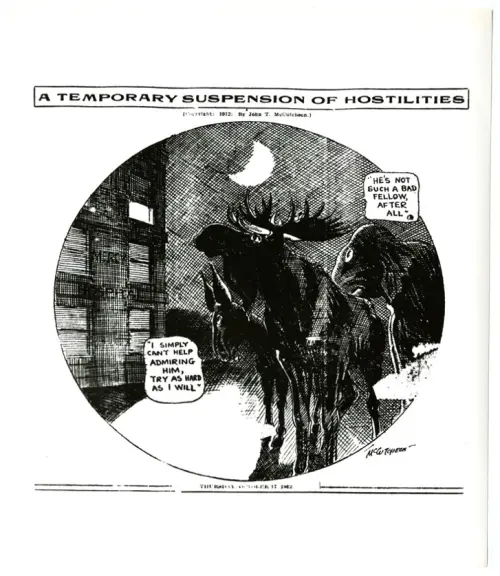

The spectacle turned tragedy into triumph, briefly galvanizing sympathy for his cause. Even his opponents temporarily suspended their campaigns for a week in recognition of Roosevelt’s injury.

As Ethel, TR’s daughter, wrote in a letter to her aunt, Anna “Bamie” Roosevelt Cowles, “[Father] looks so wonderfully well its [sic] impossible to realize that he has a bullet & an open wound. . . . Encouraging reports are coming in from all over & things look better for us than they ever have.”

But the widespread sympathy could not reverse political reality: TR’s third-party run split the Republican vote, ensuring Wilson’s victory in November. Roosevelt himself even recognized this fact before he lost the election, writing to Kermit shortly after the assassination attempt, “The chances, of course, are that Wilson will win, but the circumstances of the shooting have emphasized what really ought not to have needed emphasizing, namely, that in this contest we were living up to our professions and our motto was ‘Spend and be spent . . .’”

LEGACY OF THE MILWAUKEE SHOOTING

John Schrank’s attempt to assassinate Theodore Roosevelt on October 14, 1912, stemmed from his belief that Roosevelt’s bid for a third term violated the very foundation of American democracy. In Schrank’s disturbed mind, the two-term precedent established by George Washington was sacred, and Roosevelt’s decision to run again represented a tyrant’s ambition. His delusion—fueled by political fury and the imagined ghost of President McKinley—twisted this fear into justification for murder.

While Schrank’s reasoning was the product of mental illness according to the doctors who examined him, Schrank’s obsession reflected a real anxiety shared by many Americans at the time. Roosevelt’s return to politics broke a powerful unwritten rule: that no president should serve beyond two terms. Even some of his former supporters saw his comeback as reckless and dangerous, a threat to the republic’s tradition of restraint.

Yet Roosevelt’s survival and his calm defiance after being shot turned the would-be tragedy into an affirmation of democratic resilience. The man Schrank saw as a usurper instead became, for many, a symbol of courage under fire—literally. The bullet that was meant to silence Roosevelt instead underscored his vitality and his enduring belief that leadership meant service, not power for its own sake.

In the end, Schrank failed not only to kill a man but also to halt an idea. Roosevelt’s third-term campaign may have ended in defeat, but his vision for a more active, just, and democratic America continued to shape the nation long after the smoke cleared in Milwaukee.