TOP 10 MYTHS ABOUT THEODORE ROOSEVELT + THE INVENTION OF THE TEDDY BEAR

Few stories in American history blend truth, legend, and charm quite like the tale of Theodore Roosevelt and the teddy bear. On November 14, 1902, during a hunting trip in Mississippi, Roosevelt refused to shoot a black bear that had been tied up for him. That single act of sportsmanship inspired one of the most beloved toys in history.

But over the years, the story has grown fuzzy around the edges. Here are the top 10 myths about Roosevelt and the invention of the teddy bear—and the real history behind them.

1. ROOSEVELT FOUND THE BEAR HIMSELF

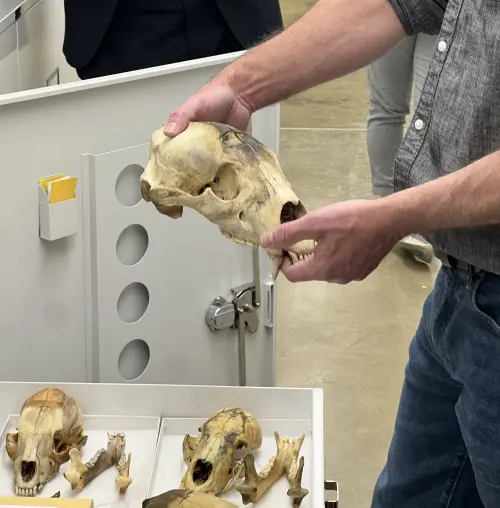

Not quite. Roosevelt’s hunting guides, including a Black man, Holt Collier, and their hounds cornered an older bear in a waterhole after several hours of tracking it through the brush. As Collier’s hunting dogs surrounded the bear, it killed one of the dogs, prompting Collier to smash the bear’s skull with the butt of his rifle.

He then captured the bear and tied up it to an oak tree for Roosevelt to shoot. When Roosevelt arrived, he saw the dead dog and the bloodied bear roped to the tree surrounded by barking dogs. The men shouted, “Let the president shoot the bear.” But Roosevelt refused and did not draw his Winchester, saying it would be unsportsmanlike to take the shot.

2. THE BEAR WAS A CUB

The real bear was a full-grown black bear, weighing 225 pounds, not the cuddly cub that appeared in later cartoons and in the American imagination. The image of a small, wide-eyed bear came later, softened for a public audience through popular media and children’s toys.

3. ROOSEVELT ORDERED THE BEAR’S RELEASE

While Roosevelt refused to shoot the bear and forbade others from shooting it, he didn’t personally release it. In fact, he did not want the animal to be tortured anymore and told the guides, “Put it out of its misery.” John Parker, later governor of Louisiana, used a Bowie hunting knife to dispatch the bear—a grim detail often left out of the popular version.

4. THE HUNT TOOK PLACE IN LOUISIANA

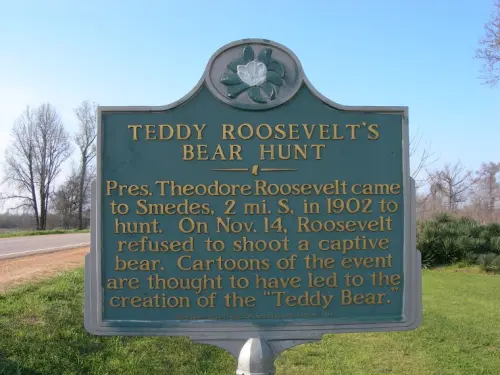

The event occurred near Onward, Mississippi, not Louisiana or Arkansas as some retellings suggest. A small marker still stands near the site today, commemorating where history and myth first met.

5. ROOSEVELT PLANNED THE INCIDENT FOR PUBLICITY

There was no political calculation behind Roosevelt’s actions. His decision came from his lifelong belief in fair play, ethical hunting, and conservation—a consistent thread throughout his public and private life. In fact, Roosevelt was disgusted with the amount of press he received during the trip.

As he wrote in a letter to his son Kermit on November 24, 1902, “I had no luck at all on my bear hunt, and I do not know that I shall go hunting again while I am President, for all kinds of people crowd after me, and it is too much like hunting with a 4th of July procession.”

Roosevelt similarly wrote to Philip Battell Stewart, “I have just had a most unsatisfactory experience in a bear hunt in Mississippi. There were plenty of bears, and if I had gone alone or with one companion I would have gotten one or two. But my kind hosts, with the best of intentions, insisted upon turning the affair into a cross between a hunt and a picnic, which always results in a failure for the hunt and usually in a failure for the picnic.”

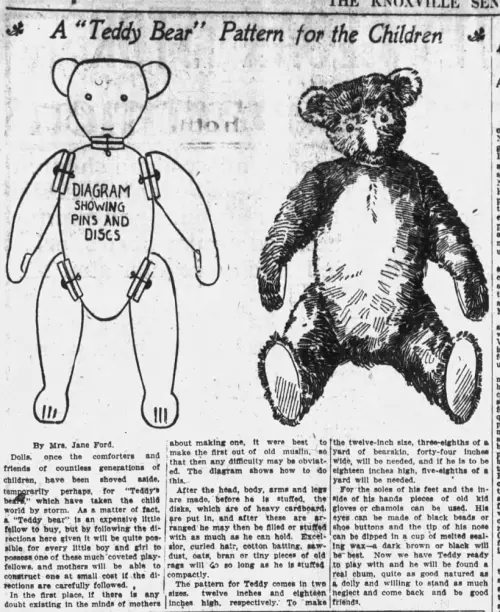

6. THE “TEDDY BEAR” WAS ROOSEVELT’S IDEA

The name and toy came from others. Inspired by the story, New York shopkeepers Morris Michtom and his wife Rose, Russian Jewish immigrants, created a stuffed bear and asked Roosevelt for permission to name it “Teddy’s Bear.”

7. ROOSEVELT PROFITED FROM THE TEDDY BEAR

Roosevelt never earned a cent from the idea. He granted the Michtoms permission to use his name, and they went on to found the Ideal Novelty and Toy Company in 1907 after several years of success with selling their bears. Their company became one of the largest toy manufacturers in the United States.

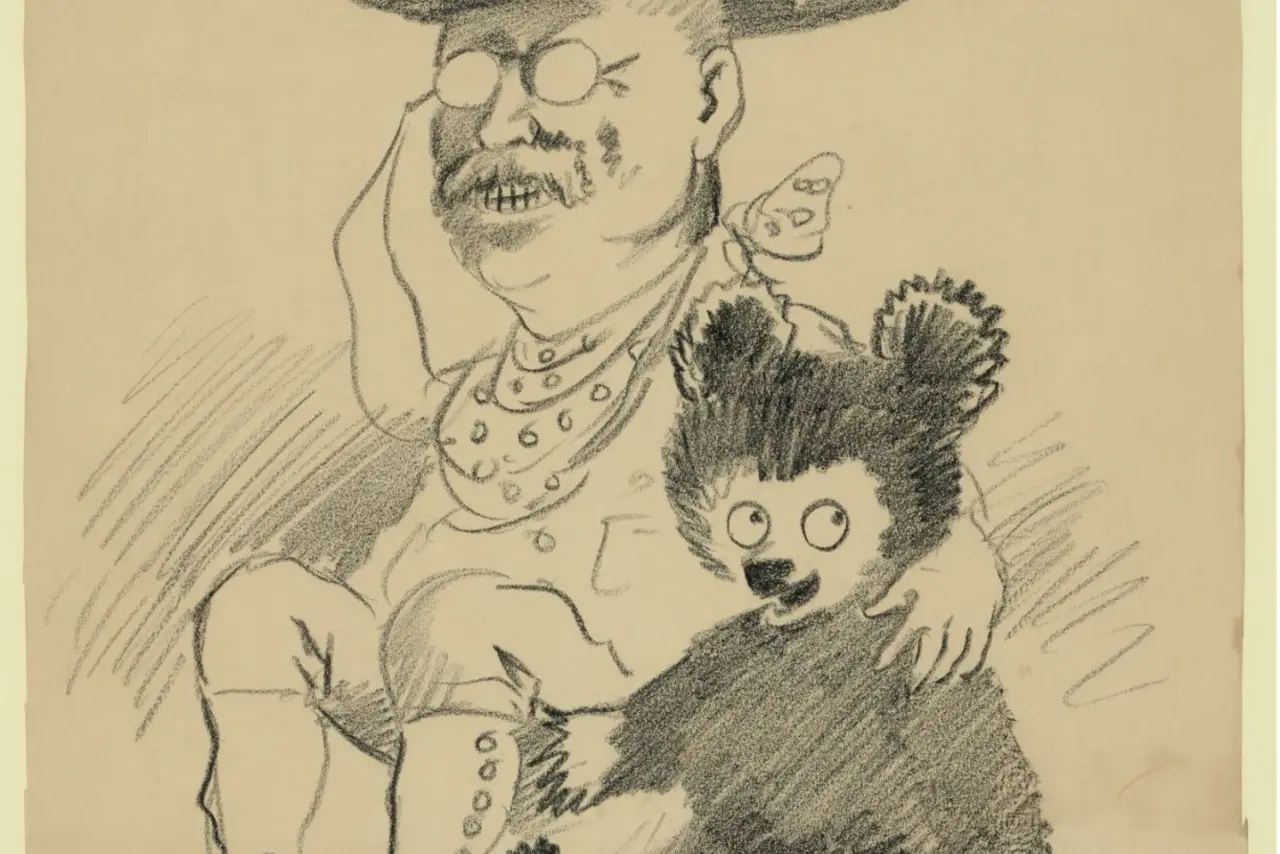

8. CLIFFORD BERRYMAN DREW THE FIRST TEDDY BEAR

Political cartoonist Clifford Berryman did draw the first depiction of the famous hunt in his cartoon “Drawing the Line in Mississippi” that appeared on November 16, 1902. Initially, the bear appeared realistic, even fierce. Over time, Berryman began drawing it smaller and cuter—the version that captured the public’s heart and Roosevelt’s as well.

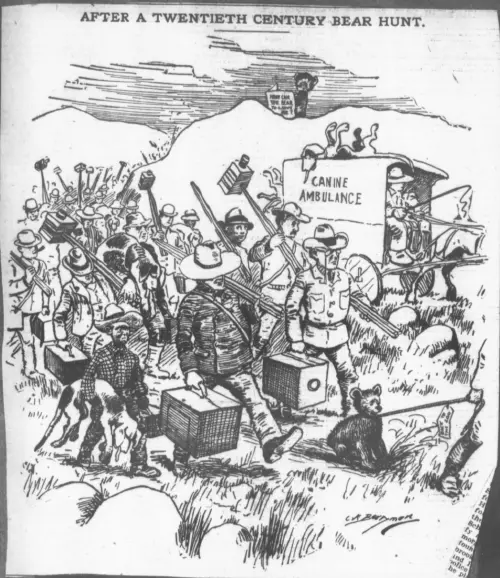

Other cartoonists also were inspired by Roosevelt’s stand, depicting the president refusing to shoot the bear in a variety of different ways. Berryman himself also drew another cartoon around the time of the hunt, “After a Twentieth Century Bear Hunt,” featuring a tied-up bear dragged before Roosevelt and an army of reporters and photographers. None of these cartoons, however, were ever as popular as Berryman’s original “Drawing the Line in Mississippi.”

Berryman also soon became known for his “Berryman bears,” which he included in almost every single political cartoon he drew related to Roosevelt going forward. And Roosevelt knew about them too! As he wrote in a December 29, 1902 letter to Berryman, “I must thank you personally for the calendar. Mrs. Roosevelt and the children will be quite as amused with it as I am. We have all been delighted with the little bear cartoons.”

9. THE TEDDY BEAR BECAME POPULAR OVERNIGHT

It took a few years for the teddy bear craze to sweep the world. Around the same time as the Michtoms debuted their bear, German toymaker Margarete Steiff began producing soft, jointed bears in Europe, helping spur the toy’s international appeal.

10. ROOSEVELT CONSIDERED TEDDY BEARS TOYS, BUT NOT DOLLS

Roosevelt received a number of toy bears from well-wishers. One example was Edna Orum, who Roosevelt called “my dear little Friend.” Replying to her letter the day after Christmas in 1902, Roosevelt wrote, “I thank you very much for the toy bear. My children will appreciate it far more than if I had succeeded in getting a bear myself. It was very nice of you to send it.” Another example was “the Teddy Bear of the Fatherland,” sent in 1905, possibly from Steiff, a German company that made teddy bears.

But Roosevelt didn’t just consider them toys; he thought they were dolls! As he wrote in response to a young girl from Binghamton, New York, Harriet Ford in 1914, “I think I must decide the bet in favor of you and against your father. I think the Teddy-bear is a kind of doll.”

A LEGACY OF SPORTSMANSHIP

The moment on November 14, 1902 when Theodore Roosevelt refused to shoot a tied bear became far more than just something that happened during Roosevelt’s time outdoors. It sparked a symbol of ethical hunting and sportsmanship that endures more than a century later.

From a Mississippi hunting camp to children’s nurseries around the world, the story of Roosevelt and the teddy bear reminds us that acts of integrity can inspire generations.