WHAT WAS THE SQUARE DEAL?

“We must treat each man on his worth and merits as a man. We must see that each is given a square deal, because he is entitled to no more and should receive no less.” ~A Square Deal, Theodore Roosevelt (1906)

After the death of William McKinley, Vice President Theodore Roosevelt became president on September 14, 1901—the youngest president in United States history. And he held true to his reputation as a reformer as he navigated the nation’s highest office, captivating the American with his Square Deal policies.

But what was the Square Deal? And did Roosevelt coin the terminology? This article will provide the answers to these questions and more.

THE ORIGIN OF THE PHRASE “SQUARE DEAL”

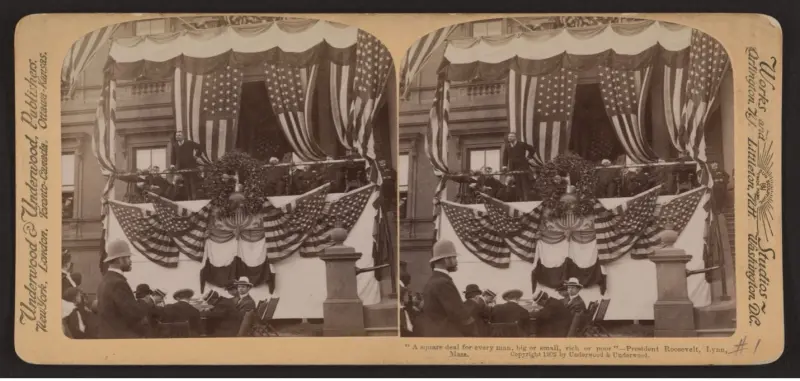

The first time Roosevelt seems to have used the phrase “square deal” was in an August 1902 speech delivered in Lynn, Massachusetts. Roosevelt did not create the phrase, but it soon became associated with the domestic policies of his presidency.

At the beginning of his presidency in 1901, there were many references to “a square deal” in newspapers across the country, but not in reference to Roosevelt. By the end of 1902, references to “a square deal” typically were connected to our 26th president.

After Roosevelt assisted in facilitating an end to the 163-day anthracite coal strike in October 1902 meditating between capital and labor, newspapers began to refer to Roosevelt’s actions as “a square deal,” implying that he had been fair to both sides.

Roosevelt himself began to use the phrase more regularly as his presidency continued, including employing it in the 1904 presidential election. In fact, one telegram Roosevelt received after winning the 1904 election read: “The people show that they love the man who always give [sic] them a square deal.”

No president before Roosevelt had ever named his domestic program, but many presidents after him followed in Roosevelt’s footsteps—Woodrow Wilson’s New Freedom, Warren G. Harding’s Return to Normalcy, Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal, Harry S. Truman’s Fair Deal, Lyndon B. Johnson’s Great Society, and Ronald Reagan’s Reaganomics.

THE THREE C’S OF THE SQUARE DEAL

When discussing Roosevelt’s presidency, historians have used the phrase “square deal” to apply to any action he took that was particularly focused on fairness and equality. In more recent years, historians have encapsulated Roosevelt’s square deal for Americans around three components—often called the three Cs: corporate regulation, consumer protection, and conservation of natural resources.

The anthracite coal strike settlement of 1902 was just one of many examples of corporate regulation where Roosevelt took on big (and often wealthy) companies and tried to find middle ground between corporations and workers.

Roosevelt made it clear, however, that he did not target large companies just because they were large—but because they had an overreach of power and needed government regulation to protect the welfare of society.

As Roosevelt wrote in A Square Deal (1906), “Treat each man according to his worth as a man. Don’t hold for or against him that he is either rich or poor. But if he is rich and crooked, hold it against him; if not rich but crooked, then hold it against him. But if he is a square man, stand by him.”

Other examples of Roosevelt’s trust busting and corporate regulation include the Hepburn Act of 1906 which gave the Interstate Commerce Commission the authority to regulate railroad rates. Roosevelt was instrumental in the passage of the act, and he worked with both sides of the aisle to develop improved government regulation of the railroad industry. He preferred better regulation to either complete government control of the railroads or a lack of any government regulation that would allow railroad companies free rein.

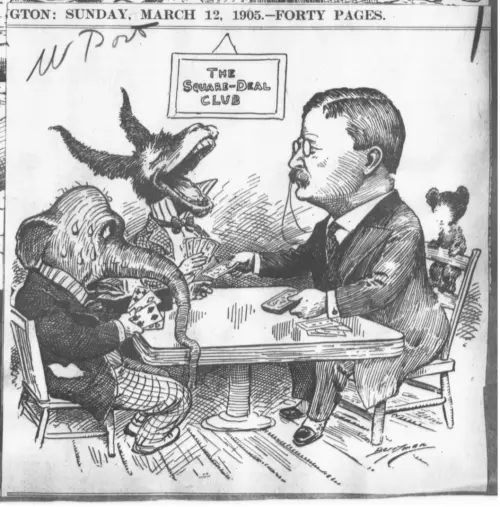

Related to corporate regulation was consumer protection, embodied by the passage of the Meat Inspection Act and Pure Food and Drug Act, which Roosevelt signed on the same day—June 30, 1906.

Spurred in part by Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle, which detailed the unsanitary conditions in the meat packing industry based in Chicago, Illinois, Roosevelt pushed for legislative reform to protect the American consumer with regard to food—meat and more.

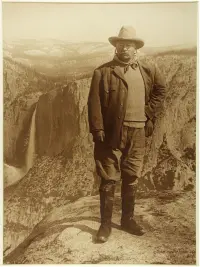

Finally, conservation is perhaps Roosevelt’s greatest legacy. He believed strongly in every American citizen having the chance to experience the outdoors through public lands and used his executive power to promote this agenda.

THEODORE ROOSEVELT’S REFERENCES TO THE SQUARE DEAL

During his presidency, Roosevelt used the phrase “square deal” regularly after 1902. Many times he used the phrase referred to his policies toward the American public as a whole. In an August 1904 letter to Ray Stannard Baker of McClure’s Magazine, Roosevelt called “a square deal for every man” his “favorite formula.”

However, he also used the phrase to discuss specific groups of American citizens like African Americans. In a speech delivered on May 27, 1903, in Butte, Montana, Roosevelt stated, “In Santiago [Cuba] I fought beside the [African American] troops of the 9th and 10th Cavalry. If a man is good enough to have him shot at while fighting beside me under the same flag, he is good enough for me to try to give him a square deal in civil life; more than that I will give no man and less than that I will give no man.”

Roosevelt saw a square deal as a key component of his presidency. As he wrote in a 1904 letter, “[I]f there is one thing that I do desire to stand for it is for a square deal, for an attitude of kindly justice as between man and man, without regard to what any man’s creed or birthplace or social position may be, so long as, in his life and in his work, he shows the qualities that entitle him to the respect of his fellows.”

Even after he left the presidency, Roosevelt employed the phrase “square deal” to refer to fairness and equality in different areas from his desire to have a square deal at the Republican National Convention in June 1912 (and his belief he would get the nomination if there were a square deal) to suggesting he gave Germany “a square deal” in articles he published in 1914.

WHAT THE PUBLIC THOUGHT ABOUT THE SQUARE DEAL

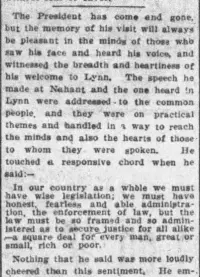

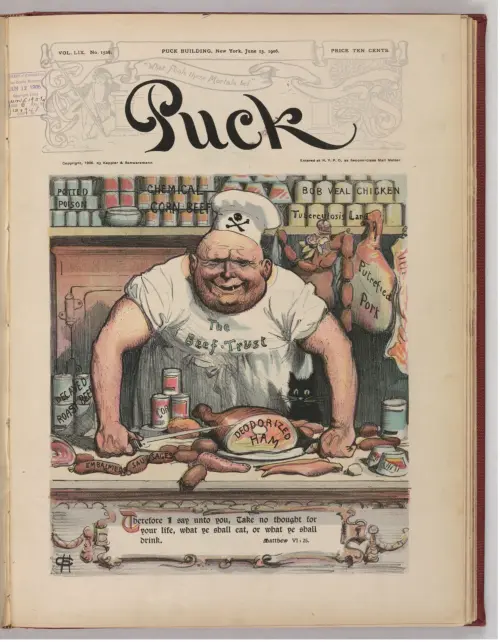

By the second half of Roosevelt’s first term, the American public had begun to connect the phrase “a square deal” with Roosevelt. The phrase appeared in newspaper articles and cartoons that featured the president and his policies.

A more unusual example where the phrase was employed was sheet music. In 1905, the Harris-Goar Jewelry Company used “a square deal” as a basis for an advertising song and included an illustration of Roosevelt on the cover.

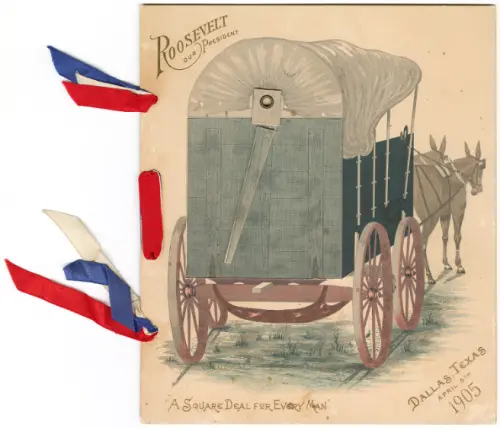

Another example of the phrase’s popularity is its appearance on a dinner program for a banquet held in Roosevelt’s honor in Dallas, Texas, on April 5, 1905.

American citizens even wrote letters to Roosevelt asking for a “square deal,” when they felt they had been wrongfully treated. One example from July 1906 published in The National Provisioner suggested that Roosevelt did not give the meatpacking industry a “square deal” and thus had wronged the Chicago packinghouses.

Whether used in a positive sense or a negative one, “a square deal” was firmly associated with Roosevelt and his ability to issue “a square deal” to every man or woman by the end of his presidency.

THE SQUARE DEAL TODAY

Politicians and the press today will occasionally reference “a square deal” when discussing current presidential administrations and comparing them to Roosevelt’s presidency. One example is Barack Obama’s 2011 speech in Osawatomie, Kansas, the location where Roosevelt delivered his “New Nationalism” speech in 1910 that discussed the square deal.

In Obama’s speech, he harkened back to the square deal, saying, “I believe that this country succeeds when everyone gets a fair shot, when everyone does their fair share, and when everyone plays by the same rules. . . . Those aren’t Democratic or Republican values; these aren’t 1 percent values or 99 percent values. They’re American values, and we have to reclaim them.”

Like so many other phrases Roosevelt either coined or popularized, “a square deal” is one that remains relevant today. Whether the sentiment is coming from a Republican in the early 1900s or a Democrat in the 2010s, Americans believe they deserve a square deal.