DID THEODORE ROOSEVELT SAVE THE BISON?

By the late 19th century, the North American bison was on the edge of extinction. Once numbering 30-60 million when Europeans first came to the United States, the great herds of the plains had dwindled to only a few hundred animals.

This near extinction occurred due to a number of reasons: market hunting, expanding railroads, habitat loss, and government policies intended to destroy Indigenous food sources. The magnitude of the slaughter was unprecedented.

It equated to two or more bison killed nonstop every minute of every day of every week of every month of every year for forty years between 1860 to 1900. Roosevelt himself was part of this buffalo killing boom, killing his first bison in 1883 at the age of 24 in Montana at Little Cannonball Creek, though he was at the tail end of the extermination of the bison.

By 1889, only 1,091 bison remained, according to the census conducted by William T. Hornaday in The Extermination of the American Bison.

Today, visitors to museums, parks, and tribal lands routinely encounter healthy bison herds. How did this remarkable turnaround happen—and did Theodore Roosevelt truly “save” the species?

The answer is yes—partly. Roosevelt played a crucial role, but the rescue of the bison was a collaborative effort spanning many decades. His legacy rests not on being the lone savior, but on building the political, scientific, and public framework that allowed the species to survive.

A SPECIES IN CRISIS

As people became more aware of the near extinction of the bison, various individuals argued for bison conservation on a federal level between 1870 and 1890. Unfortunately, all efforts fell flat.

In response to a lack of government intervention, a variety of conservation organizations were founded in the late 1800s and early 1900s to address the increasingly pressing need for wildlife protection and preservation.

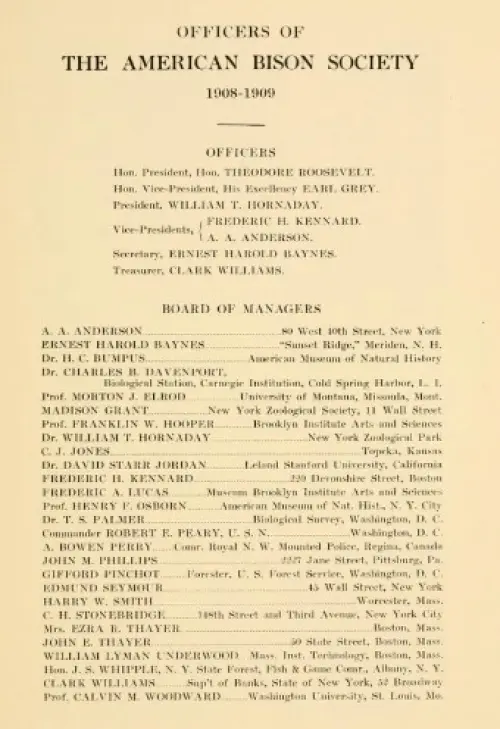

One organization was the Boone and Crockett Club, which Roosevelt himself helped found in 1887. Another was the American Bison Society, founded in 1905 to raise public awareness about the bison and to save the species from extinction.

Their plan was to purchase bison and reintroduce them into the wild. The first bison reintroduction occurred in 1907 when fifteen bison were shipped from the New York Zoological Park (known today as the Bronx Zoo) to the Wichita Mountains Wildlife Refuge and Game Preserve in Oklahoma.

ROOSEVELT THE ADVOCATE

When the American Bison Society approached Roosevelt in 1907 and asked for his support during their second campaign to raise funds for a Montana National Bison Herd, the president was happy to oblige.

By this time, Roosevelt had begun to realize the importance of wildlife conservation and had worked to change how Americans thought about wildlife. Through speeches, magazine articles, and leadership in the Boone and Crockett Club, he promoted a groundbreaking idea: wildlife was not unlimited, and the nation had an ethical responsibility to conserve it.

This shift in public mindset was essential. Conservation was new; the idea of protecting a species for future generations newer still. Roosevelt helped bring these concepts into the mainstream.

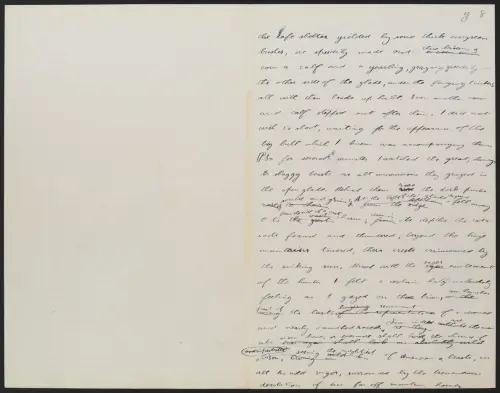

As early as the 1890s, Roosevelt had begun to recognize the plight of the bison in particular, writing in a handwritten draft of a chapter on bison for Hunting the Grisly and Other Sketches, “Mixed with the eager excitement of the hunter I felt a certain half-melancholy feeling as I gazed on these bison, themselves part of the last remnant of a doomed and nearly vanished race.”

By the early 1900s and his presidency, Roosevelt wanted to do more to bring an end to the extermination of the bison. Roosevelt became the first sitting president to argue for the preservation of the bison in his Fourth Annual Message in 1904, saying: “We owe it to future generations to keep alive the noble and beautiful creatures which by their presence add such distinctive character to the American wilderness.”

ROOSEVELT THE CHAMPION

Two years later in 1906, Roosevelt stated unequivocally in a letter to Roy N. Dunn that white men were most culpable in the near extermination of the bison, stating he had seen it firsthand: “The extermination of the American bison in the fifteen years culminating in 1883 had nothing whatever to do with climatic conditions. It was due to the number of hunters; the man with the rifle was the sole appreciable active force.”

Grouping himself in the category of people who contributed to the near extermination of the bison, Roosevelt seemed to acknowledge his culpability as well.

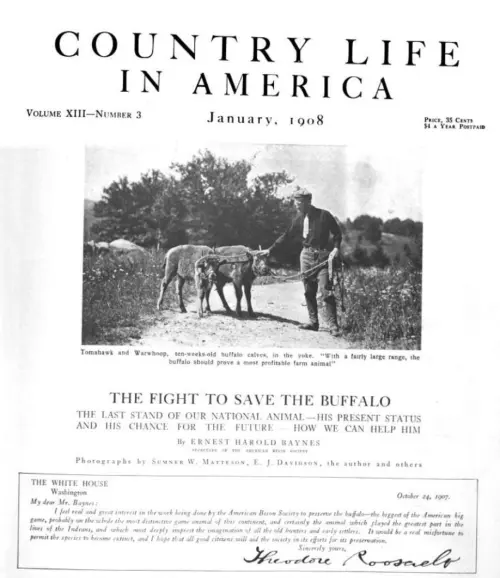

Thus, when Ernest Harold Baynes, secretary of the American Bison Society, wrote to Roosevelt on behalf of the organization on October 22, 1907 asking for a short letter to include in Country Life in America, Roosevelt replied back two days later, expressing support for the organization and its mission: “It would be a real misfortune to permit the species to become extinct, and I hope that all good citizens will aid the society in its efforts for its preservation.”

Country Life in America published this letter in the January 1908 issue at the beginning of an article by Baynes entitled “The Fight to Save the Buffalo.” The American Bison Society invited both men and women to join the cause and raise funds for the Montana National Bison Herd, stating: “The American Bison Society is trying to accomplish a work which will benefit the whole country, and it asks the whole country to bear a hand.”

THE ROLE OF WOMEN IN SAVING BISON

Intriguingly, American Bison Society leaders didn’t expect women to be interested in bison conservation. William Temple Hornaday, first director of the New York Zoological Park, noted with surprise in the 1908-1909 annual report: “Notwithstanding the widespread interest taken by women in the protection of birds, it was not expected (by the undersigned) that the plan for the creation of a national bison herd in Montana would strongly appeal to them.”

In fact, 112 women contributed over 10 percent of the funds, donating $1,227.00 of the $10,560.50 raised that year for the ABS (or roughly $40,000 out of $350,000 in today’s dollars) according to the 1908-1909 annual report.

The first subscription for the Montana National Bison Herd came from a woman—Emma L. Mee—and the person who raised the second largest sum via subscriptions “outside of the President’s office” was Ethel Randolph Clark Thayer (known as Mrs. Ezra R. Thayer). Thayer was elected to the Board of Managers and appears to be the only woman of the twenty-six members.

WHAT THE AMERICAN BISON SOCIETY ACCOMPLISHED

Thanks to the financial support of Americans across the country and the efforts of pioneering conservationists like Roosevelt, Baynes, and Hornaday, the American Bison Society worked with several organizations in the early 1900s to reintroduce bison into the wild.

The Montana herd for which the ABS raised subscriptions from 1908 to 1909 was sent to the National Bison Range in Montana in 1910—located inside the Flathead Indian Reservation. The range had been established out of a portion of the reservation on May 23, 1908, when Roosevelt signed legislation authorizing the use of funds to purchase this land for bison conservation after Congress appropriated the money to buy land specifically for wildlife conservation—the first act of its kind.

Initially, in the late 1800s and early 1900s, Michel Pablo and Charles Allard had managed the bison herd on the Flathead Reservation in Montana before the creation of the National Bison Range until the Flathead Allotment Act of 1904 caused the loss of sixty percent of the reservation for the Confederated Tribes of the Salish and Kootenai.

After an inability to maintain the bison herd on the allotted land, Pablo tried to sell his herd to the US government, but Congress refused to purchase it. Pablo instead sold his herd to the Canadian government in 1907. Some of the Pablo-Allard herd did make it to the newly created National Bison Refuge. Of the forty bison that formed the original herd, thirty-six were connected to the Pablo-Allard herd, at one time the largest herd of plains bison in the world.

Little thought was given to the reduction of the Salish and Kootenai peoples’ homeland when the range was created. It wouldn’t be until 2021—113 years later—that the land that comprised the National Bison Range, approximately 18,800 acres, was returned to the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes who are now stewards of the bison herd.

A COLLABORATIVE TRIUMPH

Today the bison is alive and well in the United States. Declared America’s national mammal by President Barack Obama in 2016, the bison continues to capture the American imagination. A lot of work has been done in the past 150 years to save the bison, but it is a continual process to make sure that gains aren’t lost.

Although Roosevelt was a driving force, he did not work alone. Private ranchers such as Charles Goodnight, the Dupree family, and the Pablo-Allard partnership preserved small herds when few others cared.

Indigenous nations maintained cultural, spiritual, and historical connections to the bison even as colonial policies devastated their lands. Today, many tribal communities lead bison-restoration programs, continuing a stewardship tradition that long predates Roosevelt.

Scientists and wildlife managers built on early breeding programs to re-establish conservation herds across the country. The survival of the bison was, and remains, a cooperative endeavor.

THE BISON TODAY

Today, roughly one-third of all wild bison—numbering around 10,000—in North America live in herds on public lands. Although bison are no longer endangered, discussions surrounding rights and responsibilities of bison hunting, the species itself, and its habitat exist to this day.

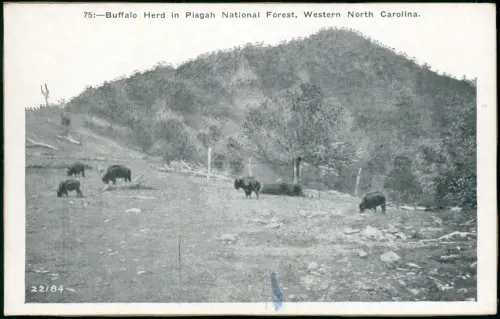

The American Bison Society of Roosevelt’s day continued to reintroduce bison into the wild with the last reintroduction occurring in the Pisgah National Forest and Game Preserve in North Carolina in 1919. The organization was disbanded in 1935 when it was determined that the species had been successfully saved.

However, the organization experienced a rebirth in 2005 when the Wildlife Conservation Society relaunched the American Bison Society with a new focus: to promote the preservation of the species for the future.

Other modern efforts for bison conservation occurred around the same time with the establishment of a large-scale prairie restoration initiative in Montana in 2001 that is now known as the American Prairie Reserve. This is one of many efforts to restore the habitat of the bison and to create the largest wildlife reserve in the continental United States.

DID ROOSEVELT SAVE THE BISON?

Without Roosevelt’s influence, the bison might have vanished from the United States. Roosevelt’s leadership was instrumental in providing the following:

- National visibility for the crisis

- Early legal protections for bison and their habitat

- Support for scientific management

- Creation of a refuge dedicated specifically to bison recovery

- A new conservation ethic embraced by future generations

But Roosevelt’s conservation efforts to save the American bison weren’t perfect. While his use of the presidential platform to increase public awareness of the need to preserve the bison made a difference in the fight to save the bison, his actions also had ramifications for Indigenous people across the country, as their homelands were often taken from them.

Today Indigenous people have a greater voice in bison conservation than they did in the early 1900s. Cristina Eisenberg, an Indigenous ecologist, noted in an article about bison conservation for the Smithsonian magazine, “Bison conservation will not succeed unless it is in collaboration with Native people and incorporates traditional ecological knowledge . . . . That empowers those communities and it honors them and helps heal some of the damage that has been done – the genocide and all of that.”

The revival of the species is a story larger than any single leader—a tapestry of private effort, tribal stewardship, scientific innovation, and long-term public commitment. The bison’s recovery is ongoing, shaped by questions about genetics, disease management, cultural restoration, and land stewardship. But it remains one of the great success stories in global conservation—rooted in the vision Theodore Roosevelt championed more than a century ago.