WHAT WERE THEODORE ROOSEVELT’S FIVE SIGNIFICANT ACCOMPLISHMENTS PRIOR TO BECOMING PRESIDENT?

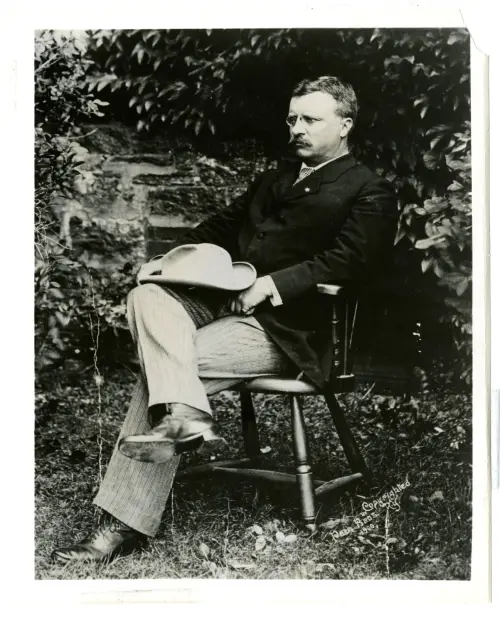

Theodore Roosevelt is best remembered as one of America’s most popular presidents, a man whose legacy reshaped conservation, diplomacy, and the role of the modern executive. But Roosevelt’s rise to the White House was built on a foundation of remarkable accomplishments before he ever stepped into the Oval Office.

By the time he assumed the presidency in 1901 after the assassination of William McKinley, Roosevelt had already served in a variety of political roles. He had been a crusader in Albany, New York, a national reformer in Washington, DC, a fearless commissioner in New York City, a naval strategist, and finally governor of the most populous state in the Union. His presidency was a natural continuation of a life already packed with bold action in politics.

1. NEW YORK ASSEMBLYMAN (1882-1884): ROOSEVELT REFORM BILLS

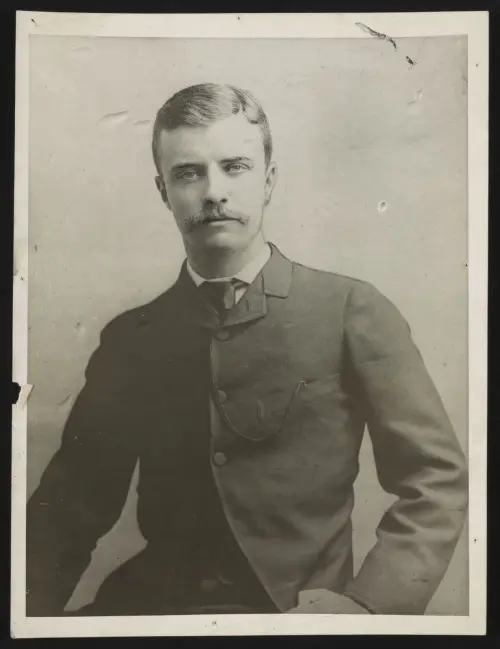

Roosevelt’s public career began in 1881 when, at just 23, he was elected to the New York State Assembly. A young man of privilege from Manhattan, Roosevelt could easily have spent his life in comfort. Instead, he hurled himself into the rough-and-tumble world of Albany politics.

In the Assembly chamber, he quickly stood out, establishing himself as a reformer determined to challenge entrenched political machines that had long dominated state government. His voice, described as high-pitched but forceful, rang out as he demanded accountability from party bosses and corporate interests alike. The New York Journal called him the “Cyclone Assemblyman.”

At first, other Assembly members weren’t sure about the new addition, particularly those who believed Roosevelt should tow the Republican Party line. However, as time went on, he did gain friends and allies. As Charles Eugene Banks and Le Roy Armstrong wrote in 1901, “He was one of that company of reformers in both great parties, of which George William Curtis, Senator Edmunds and Grover Cleveland, the latter then governor of New York, were members.”

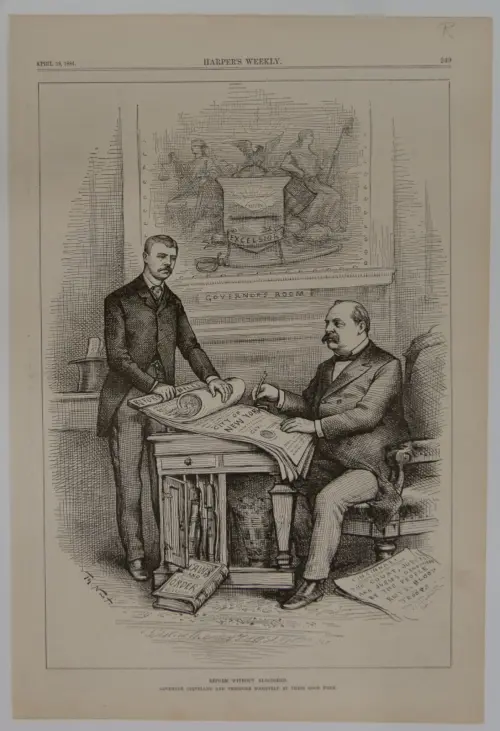

One of Roosevelt’s most important contributions from his time as an assemblyman was the passage of the municipal reform bills for New York City. As he wrote in a May 1884 letter, “This winter my main work has been pushing the Municipal Reform bills for New York City; in connection with which I have conducted a series of investigations into its various departments. Most of my bills have been passed and signed [by Governor Grover Cleveland].”

The bills that Roosevelt references “which provided for a complete change in the old system under which the corrupt politicians of both parties had been robbing the city for many years” were so connected to Roosevelt that they became known as the Roosevelt reform bills, or simply the Roosevelt bills, and they sought to address overreach of various city positions.

Many publications during Roosevelt’s time and after referred to the bills with this language, including The Continent, an illustrated weekly magazine, which noted on April 16, 1884: “After full discussion in the Assembly and many amendments having been voted down the six Roosevelt reform bills were passed by very large majorities.” Governor Grover Cleveland did not sign all of them, including vetoing office and park department bills.

These bills were just one example of Roosevelt establishing himself as a fearless fighter for honesty and transparency during his two-year tenure in the legislature. For the first time, the public caught a glimpse of the fiery young reformer who would not bend to corruption or convenience.

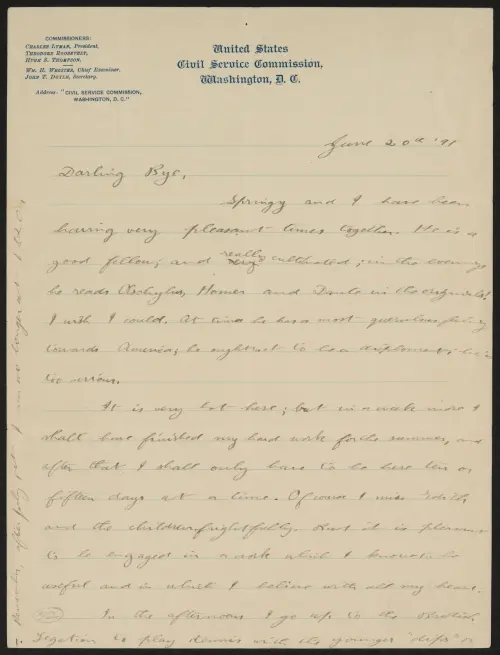

2. US CIVIL SERVICE COMMISSIONER (1889-1895): RACIAL EQUITY FOR GOVERNMENT EMPLOYEES

By 1889, Roosevelt had carried his reformist instincts to Washington. Appointed by President Benjamin Harrison to the US Civil Service Commission, he found himself in charge of overseeing federal jobs at a time when political favoritism still ruled and those in power rewarded friends and allies. For most officials, the position of civil service commissioner was sleepy and symbolic. Roosevelt turned it into a battleground.

He insisted that jobs be awarded on merit, not political loyalty. His push for competitive exams and his investigations into corruption rattled members of both parties. Roosevelt loved the fight. He did not shy away from the unpopularity that came from clashing against entrenched interests.

Roosevelt’s efforts paid off. By the time he left the commission six years later, the civil service had become more professional, and corruption was rooted out in several agencies. As Thomas Herbert Russell wrote in Life and Work of Theodore Roosevelt (1919), “When [Roosevelt] became president of the Civil Service Commission 14,000 Government offices were under Civil Service rules; when he left, in 1895, to run the New York police, 40,000 offices were under Civil Service rules, and the increase was due chiefly to his energy and persistence.”

Roosevelt also earned a national reputation as an honest man who refused to play politics as usual. Newspapers even started referring to him not as Theodore Roosevelt or even as TR, but by his now well-known nickname, “Teddy.” They did so sometimes because it made him seem more approachable, but other times to ridicule him.

By insisting on merit-based appointments, one of Roosevelt’s biggest accomplishments as a civil service commissioner was promoting racial equity among government employees. As Edward Stratemeyer wrote in American Boys’ Life of Theodore Roosevelt(1904), “One of the best and wisest acts of the Commission was to place the [Black] employees of the government on an equal footing with the white employees.”

Roosevelt himself was praised in an African American newspaper, the New York Age, in May 1895 for his emphasis on merit-based appointments and competitive exams. Roosevelt had appointed close to 100 Black clerks in the US government, causing Robert H. Terrell, the first Black judge in the Washington, DC Municipal Court and a Harvard-educated lawyer, to observe that “[n]o one had done more than Roosevelt for the cause of improving government.”

Roosevelt also fought against flagrant racism. In 1894, the Commission received reports of significant numbers of Black women removed from the Bureau of Engraving and Printing for no apparent reason. It investigated the matter and sent a report to the Secretary of the Treasury about the “very marked discrimination on grounds of color merely.”

Because the Chief of the Bureau of Engraving and Printing said there was no discrimination, there was nothing else Roosevelt and the Civil Service Commission could do. But they did include one final line in their report to Congress, which was attributed to Roosevelt: “[The commission] did not believe that the line of cleavage between efficiency and inefficiency could by a mere coincidence so closely follow the color line, not to speak of the passing over of colored women in making selections from the certifications of eligibles.”

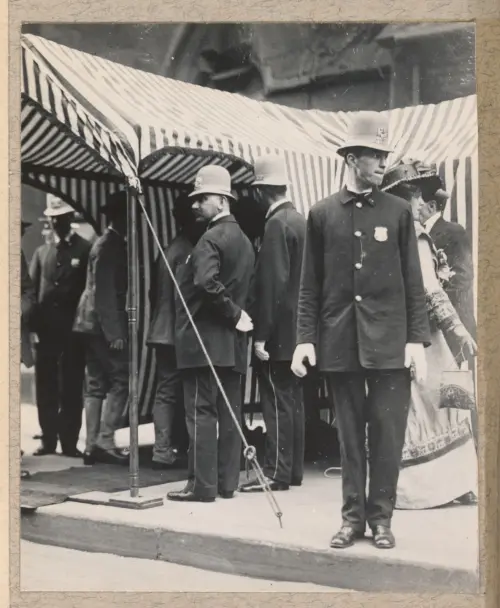

3. PRESIDENT OF THE BOARD OF POLICE COMMISSIONERS (1895-1897): WAR ON BANANA PEELS

Roosevelt’s next great challenge came in 1895 when he was appointed president of the New York City Police Board. Where others saw a hopeless mess, Roosevelt saw an opportunity. The city’s police force was notorious for graft—officers accepted bribes from saloonkeepers, gamblers, and brothel owners in exchange for protection. Roosevelt intended to correct that.

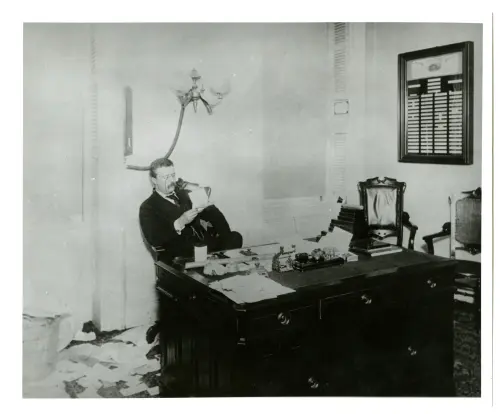

Plunging into the work with his usual intensity, he demanded stricter standards for hiring, promoted men of ability rather than influence, and launched a campaign against bribery. But he didn’t just sit in an office—he patrolled the streets himself.

Night after night, Roosevelt would leave his home, slip into a dark overcoat, and walk the midnight beats. To the shock of the rank-and-file, the commissioner himself would suddenly appear out of the shadows. If he caught officers sleeping, drinking, or neglecting their posts, he would bark at them in the middle of the street.

The press delighted in the stories, and the public began to see Roosevelt as a new kind of reformer: not just one who issued orders, but one who enforced them in person. His insistence on evenhanded law enforcement—closing saloons on Sundays, no matter the owner’s influence—earned him enemies, but also deep respect. (One such enemy was John Schrank, who attempted to assassinate Roosevelt in 1912. Schrank reported to police that Roosevelt had closed his family’s liquor business.)

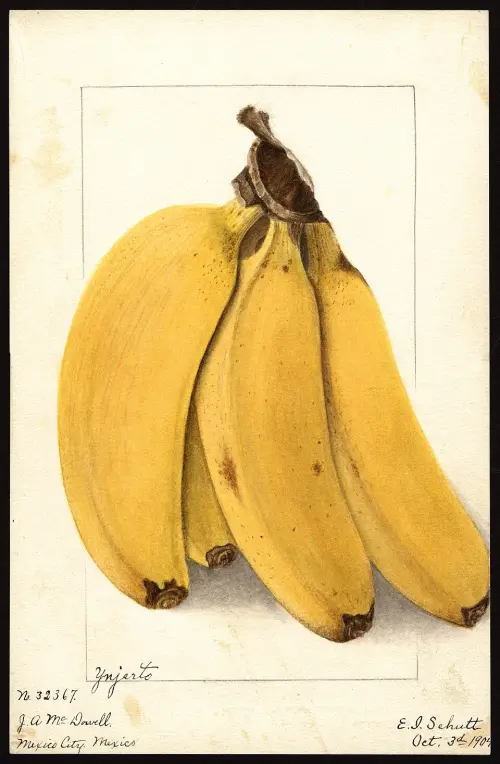

Roosevelt cared so much about public safety that he even took on banana peels as police commissioner. Yes, you read that correctly! In 1896, Roosevelt became aware of the dangers of stray banana peels, apple skins, and potato skins on the pavement and decided to take action.

As the New York Herald wrote on January 18, 1896, “Now that a young man has broken his leg by a fall caused by stepping on a banana skin, the police ought to be instructed to look out for people who peel bananas in the street and fling down the skin. . . . If a few of them were arrested and punished, the offence [sic] would be done away with. It is an offence [sic], in violation of city ordinance.”

Less than a month later on February 8, 1896, Roosevelt assembled captains, sergeants, and roundsmen of the police force and explained “the bad habits of the banana skin, dwelling particularly on its tendency to toss people into the air and bring them down with terrific fore on the hard pavement.”

Roosevelt read from the city ordinance about those who littered fruit or vegetables in the street, noting they could be fined up to $5.00 (or close to $200 today!) and serve 10 days in jail, and told the police officers to enforce those laws regarding litter and clean up the streets.

Although making sure the streets were free of banana peels and other fruit and vegetable skins is more light-hearted than some of Roosevelt’s other reforms, it reveals how serious Roosevelt was about public safety and the enforcement of laws.

4. ASSISTANT SECRETARY OF THE NAVY (1897-1898): MODERNIZING THE NAVY

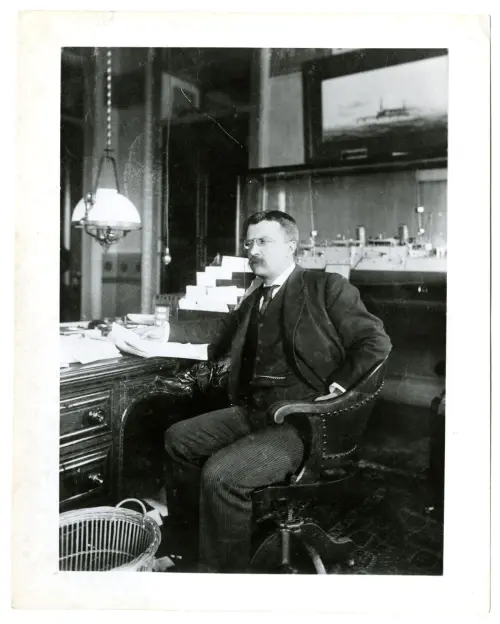

In 1897, Roosevelt entered a new stage of his career when President McKinley appointed him Assistant Secretary of the Navy. A lifelong student of naval history, his first book, The Naval War of 1812, published in 1882 when Roosevelt was 24 years old quickly became a definitive history of the naval aspects of the war. Even at this young age, Roosevelt became nationally recognized as a naval expert—several years before Alfred Thayer Mahan emphasized the importance of the Navy.

Now, as Assistant Secretary of the Navy, Roosevelt had the chance to put theory into practice. Roosevelt had long believed that America’s future depended on a strong, modern navy, drawing heavily on Mahan’s ideas in The Influence of Sea Power upon History, published in 1890, and he immediately set about making his vision a reality.

Roosevelt had a holistic view of what he believed was needed to establish the United States Navy as a force with which to be contended. He pushed for new battleships, improved training, and more efficient administration.

His push for appropriations for marksmanship provided naval crews with gun practice. Roosevelt received his first request for $800,000—or roughly $31 million in today—shortly after his appointment as assistant secretary. However, when he asked for another appropriation of $500,000—or roughly $19 million today—he was asked what happened to the first appropriation and what would happen with the second.

Roosevelt reportedly replied, “Every cent of it has been spent for powder and shot, and every bit of powder and shot has been fired. . . . [And I would use] every dollar of [the second appropriation], too, within the next thirty days in practice shooting.”

Because Roosevelt anticipated conflict with Spain over Cuba, his preparations paid off. Thanks in part to his advocacy, Commodore George Dewey’s fleet in the Pacific was ready when war came in 1898, leading to the stunning American victory at Manila Bay.

As Frederick E. Drinker and Jay Henry Mowbray wrote in Theodore Roosevelt: His Life and Work (1919), “It cost something to turn a raw middy into a good gunner, but it was a good investment. In the battles that followed, the ‘men behind the guns’ won the victories, and they did it because they knew how to shoot.”

More significantly, Roosevelt’s pushing through of appropriations for the new steel ships and creating refueling stations across the world had an even larger impact. After the American Civil War, the US Navy had declined sharply. By the 1880s, it was a “third-rate” navy, smaller than those of modernizing European powers like Britain, France, Germany, or even Italy. Most ships were wooden or outdated ironclads from the Civil War era. Only a handful of modern steel ships existed. It was primarily a coastal defense force.

Roosevelt knew that to become a world power the United States needed a new naval strategy that promoted the expansion of the Navy, which could not occur without an updated fleet. Thanks to the efforts of Roosevelt and others, the Navy was ushered into the modern era with naval construction emphasizing the creation of battleships.

In particular, after the Spanish-American War in 1898, the conflict that brought Roosevelt to national prominence, the United States fully recognized its need for a strong Navy and transformed its naval policy, turning the US into a modernized world power.

5. GOVERNOR OF NEW YORK (1898-1900): LABOR LAWS

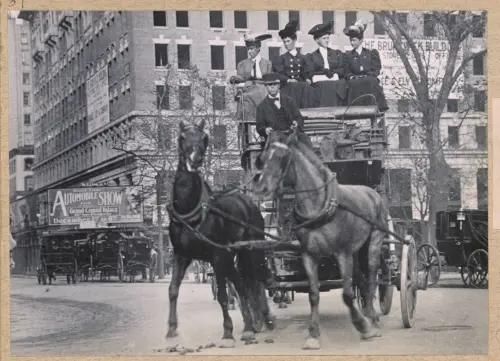

In addition to jumpstarting the urgency for a modern Navy, the Spanish-American War also ushered in a new political leader known across the United States. Thanks to his courage in the war, Roosevelt rose in national prominence, leading to his ultimately successful gubernatorial campaign in New York. After he was elected governor in November 1898, Roosevelt quickly became known as a reformer and as someone who did not feel the need to obey party bosses.

One of his most significant contributions as governor was working to pass labor laws. Roosevelt specifically included a section entitled “labor interests” in his Governor’s Message on January 2, 1899, noting that in some cases, government regulation was needed to benefit both laborers and employers and put forth a few suggestions to ensure that the laws on the books were enforced.

Within his first six months as governor and slightly over five months after his Governor’s Message, Roosevelt pushed forward an eight-hour-day law that protected all state employees. As Roosevelt wrote in a memorandum for the Assembly bill: “This bill carries out the recommendation made in my message to the Legislature that the eight-hour law should be so amended as to make it effective. . . . I accordingly sign the bill.”

In total, Roosevelt signed seventeen laws that benefitted labor during his time as governor, which gained him much support from labor. The Republican Campaign Text-book from 1904 details what he did for labor as governor of New York in the section, “Epitome of Theodore Roosevelt’s Favorable Action on Labor Legislation”:

- Creating a tenement-house commission. (“Tenement” is a historic term used to describe a type of building with multiple dwellings, often characterized by poor living conditions.)

- Regulating sweat-shop labor.

- Empowering the factory inspector to enforce the scaffolding law.

- Directing the factory inspector to enforce the act regulating labor hours on railroads.

- Making the eight-hour and prevailing-rate-of-wages laws effective.

- Amending the factory act—(1) Protecting employees at work on buildings. (2) Regulating the working time of female employees. (3) Providing that stairways shall be properly lighted. (4) Prohibiting the operation of dangerous machinery by children. (5) Prohibiting women and minors working on polishing or wheels. (6) Providing for seats for waitresses in hotels and restaurants.

- Shortening the working hours of drug clerks.

- Increasing the salaries of New York City school-teachers.

- Extending to other engineers the law licensing New York City engineers and making it a misdemeanor for violating the same.

- Licensing stationary engineers in Buffalo. (Stationary engineers operated stationary machinery, including steam engines and other industrial machinery.)

- Providing for the examination and registration of horseshoers in cities.

- Registration of laborers for municipal employment.

- Relating to air brakes on freight trains.

- Providing means for the issuance of quarterly bulletins by the bureau of labor statistics.

The campaign book also notes: “In addition to the foregoing while governor of New York he recommended legislation (which the legislature failed to pass) in regard to—Employers’ liability. State control of employment offices. State ownership of printing plant. Devising means whereby free mechanics shall not be brought into competition with prison labor.”

BOLD, ENERGETIC POLITICAL LEADERSHIP

Before ascending to the presidency, Theodore Roosevelt’s political accomplishments already marked him as one of the most dynamic reformers of his era. His early career in the New York State Assembly demonstrated his fearless independence—he challenged entrenched political machines, exposed corruption, and pushed for civil service reform at a time when political favoritism dominated politics.

As New York City Police Commissioner, Roosevelt brought honesty and efficiency to a force plagued by graft, insisting that officers enforce the law equally across all classes and neighborhoods. His tenure as US Civil Service Commissioner further reinforced his reputation as a principled reformer committed to merit over favoritism.

Roosevelt’s time as Assistant Secretary of the Navy revealed his vision for America’s emerging role on the world stage, as he worked to modernize the fleet and prepare the nation for global influence. When the Spanish-American War broke out, he famously resigned his post to form the unit that became known as the Rough Riders—an act of both patriotism and leadership that captured national attention.

After his military triumph at Kettle Hill, his subsequent election as Governor of New York allowed him to implement progressive policies on labor, conservation, and corporate regulation. By the time he became William McKinley’s vice president in 1901, Roosevelt had proven himself a force of reform and energy—a man who believed government should serve the people’s welfare rather than special interests.

When President William McKinley was assassinated in September 1901, the 42-year-old Roosevelt suddenly became the youngest president in American history. In his seven-and-half years in office, he would transform the presidency, enacting daring reforms that are remembered to this day.

Roosevelt’s rise to national prominence reflected his bold, energetic leadership and his determination to make public life safer and fairer for all Americans—a prelude to his transformative presidency.